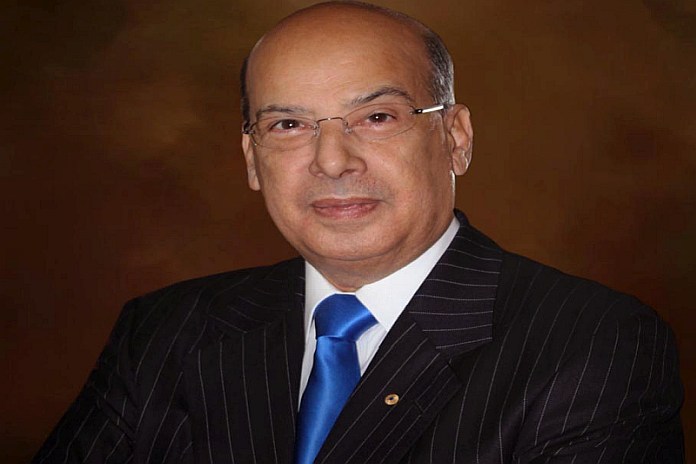

By Sir Ronald Sanders

At a meeting of the Permanent Council of the Organization of American States (OAS) on March 17, I said that “no resolution is perfect, and no resolution satisfies every country, but we cannot sacrifice achieving good on the altar of desiring perfection”.

The resolution concerned the current constitutional, political and humanitarian situation in Haiti which is very grave and shows every sign of worsening. The delegation of Antigua and Barbuda was the architect of the original resolution which sought to cause the member states of the OAS to express concern about Haiti and to offer to facilitate a meaningful dialogue between president Jovenel Moïse and all other stakeholders.

It was a matter of regret that, despite the strong statement of CARICOM heads of government, concerning Haiti, on February 11, CARICOM delegations at the OAS were again divided. CARICOM heads were clear that they wanted “all parties in Haiti to engage in meaningful dialogue in the interest of peace and stability”. The heads also said that they looked forward “to the conduct of free and fair presidential elections in accordance with the Constitution of Haiti”. Eight CARICOM countries – Barbados, Belize, Grenada, Guyana, St Kitts-Nevis, Saint Lucia, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago backed Antigua and Barbuda’s draft resolution.

In the end, through a process of two weeks of negotiations, countries with important concerns about Haiti – Brazil, Canada, Chile, the Dominican Republic, and the United States joined the nine Caribbean countries in settling a draft resolution that was then negotiated with the Haitian delegation.

By the nature of negotiations, concessions had to be made. Hence, it was not a perfect resolution and not every paragraph of it satisfied every one. But it was enough to allow the Permanent Council of the OAS to adopt it by consensus.

Essentially, it offered “good offices of the OAS, under the authority of the Permanent Council, to facilitate a dialogue that would lead to free and fair elections” and asked the president of Haiti “to consider inviting the Permanent Council to do so”.

This was done against a background that since January 2020, there has been no legislature and no government in Haiti, and president Moïse has been ruling by decree. Further, marauding gangs have been raping women, including young girls, kidnapping people (rich and poor) and demanding huge ransoms. Violence has exploded in the country, particularly as hundreds of thousands of people have been protesting against president Moïse and deadly force has been used against them by a police force that is allegedly highly politicised.

The UN High Commission for Human Rights has stated its “concerns about judicial independence” which it says “has further eroded the separation of powers” in Haiti.

Time is fast running out to avoid further worsening of the situation in Haiti. The OAS resolution, offering to facilitate dialogue, has come only after deep polarization and distrust in the country. The OAS should have acted much earlier. If president Moïse does not respond positively and swiftly to the offer by the OAS, no dialogue between the stakeholders might be possible. A stand-off between them will occur with further confrontations. Many Haitians have already stated publicly that “no dialogue is possible with Moïse”, and he has not sought a meaningful dialogue either.

Instead, he is persisting with plans to hold a referendum in June on altering the Constitution. But there has been no consultation with major Haitian players who say he has no authority to hold such a referendum. What is clear is that, in 2015, Haiti had more than 6.5 million people registered to vote. Moïse has now issued new identity cards which his OAS ambassador says has been distributed to four million people. Human rights groups in Haiti dispute that figure, putting it closer to two million. Either way, more than 2.5 million persons are currently disenfranchised. No referendum or election held in these conditions would be credible or acceptable.

Still worse, the current Provisional Electoral Council, to manage a referendum and elections, comprises persons appointed solely by Moïse. They are known to have close links to him. Similarly, the draft Constitution has been written by persons he has hand-picked. None of this is “in accordance with the Constitution of Haiti”, and, for the opposition parties, are red rags to a bull.

On March 29, Haiti will mark the anniversary of its 1987 Constitution the very thing that the president is seeking to alter. Stakeholders are pledging to put more than two million people on the streets in its defence on March 28 and 29.

The Charter of the OAS strictly forbids interference in the internal affairs of States. And, while there have been various artifices by some OAS member states to circumvent that prohibition, the majority of countries adhere to that principle generally. Consequently, the OAS cannot insist that president Moïse accepts its offer to play a good offices role. It must await an invitation from him to do so.

In this context, member states of the Organization should work behind the scenes with Moïse and other stakeholders to urge them to talk and, in so doing, to take the idea of a referendum on the Constitution off anyone’s agenda; to ensure that independent election machinery is established by agreement of all parties and that presidential, legislative and local elections are held at the earliest possible date, and until then presidential decrees should be suspended on anything except that on which major players decide.

While this diplomatic work takes place – and CARICOM should be a part of it – the OAS should continue to be vigilant about developments in Haiti and ready to speak out against any further deterioration in the constitutional, political and humanitarian situation.

The people of Haiti need and deserve objective and constructive support in their collective interest, and not for the benefit of any political elite.