By Francesca Caselli and Prachi Mishra

The economic recovery has fueled a rapid acceleration in inflation this year for advanced and emerging market economies, driven by firming demand, supply shortages, and rapidly rising commodity prices.

We forecast in our latest World Economic Outlook that higher inflation will likely continue in coming months before returning to pre-pandemic levels by mid-2022, though risks of an acceleration do remain.

The good news for policymakers is that long-term inflation expectations are well anchored, but economists still disagree about how enduring the upward pressure for prices will ultimately be.

Some have said government stimulus may push unemployment rates low enough to boost wages and overheat economies, possibly de-anchoring expectations and resulting in a self-fulfilling inflation spiral. Others estimate that pressures will ultimately be transitory as a one-time surge in spending fades.

Inflation dynamics and recovering demand

We examine if headline consumer price index inflation has moved in line with unemployment. Although the pandemic period poses many challenges to estimating this relationship, the unprecedented disturbance doesn’t seem to have substantially altered this relationship.

Advanced economies are likely to face moderate near-term inflation pressure, with the impact softening over time. Estimates of the relationship between slack, the amount of resources in an economy that aren’t being used, and inflation for emerging markets instead seem to be more sensitive to the inclusion of the pandemic period in the estimation sample.

Anchoring expectations

Inflation during the pandemic has been well anchored, according to measures of long-term expectations known as breakevens drawn from government bonds in 14 nations. These closely watched gauges have been stable so far during both the crisis and the recovery, though uncertainty about the outlook remains.

A key question is what combination of conditions could cause a persistent spike in inflation, including the possibility that expectations become unanchored and help spark a self-fulfilling upward spiral for prices.

Such episodes in the past have been associated with sharp exchange-rate depreciations in emerging markets and have often followed surging fiscal and current account deficits. Longer-term government spending commitments and external shocks could also contribute to expectations becoming de-anchored, especially in economies with central banks that aren’t believed to be able or willing to contain inflation.

Moreover, even when expectations are well anchored, a prolonged overshoot of the inflation target that policymakers have set could cause a de-anchoring of expectations.

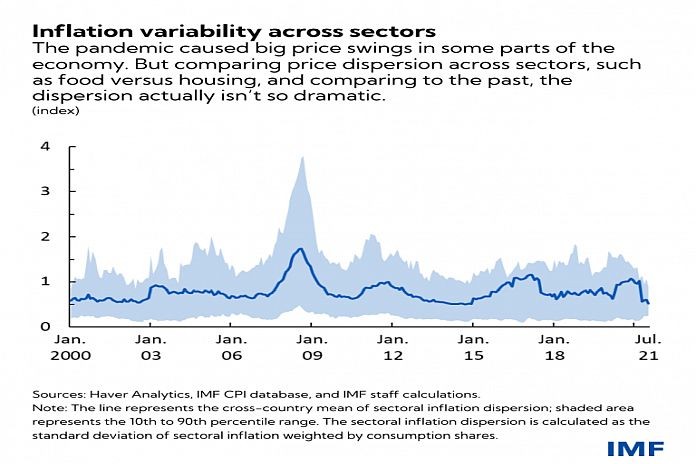

Sectoral shocks

The pandemic has triggered large price movements in some sectors, notably food, transportation, clothing, and communications. Strikingly, the dispersion or variability in prices across sectors has so far remained relatively subdued by recent historical standards, especially compared with the global financial crisis. The reason is relatively smaller and shorter-lived swings in fuel, food, and housing prices post the pandemic, which are the three largest components of consumption baskets, on average.

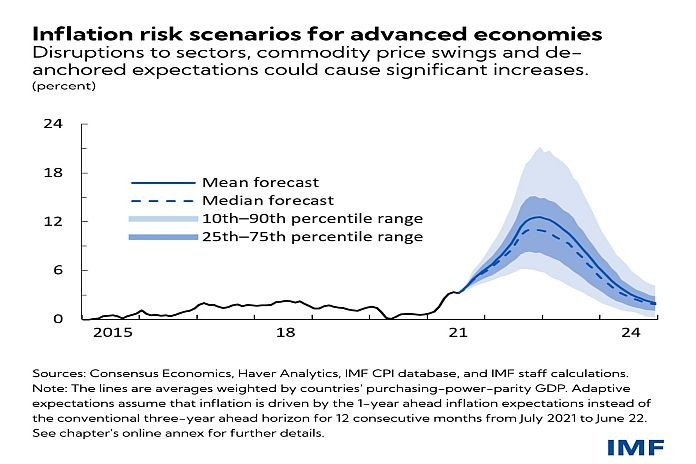

Our forecast is that annual inflation in advanced economies will peak at 3.6 percent on average in the final months of this year before reverting in the first half of 2022 to 2 percent, in line with central bank targets. Emerging markets will see faster increases, reaching 6.8 percent on average then easing to 4 percent.

The projections, however, come with considerable uncertainty, and inflation may be elevated for longer. Contributing factors could include surging housing costs and prolonged supply shortages in advanced and developing economies, or food-price pressure and currency depreciations in emerging markets.

Food prices around the world jumped by about 40 percent during the pandemic, an especially acute challenge for low-income countries where such purchases make up a big share of consumer spending.

Simulations of several extreme risk scenarios show prices could rise significantly faster on continued supply chain disruptions, large commodity price swings, and a de-anchoring of expectations.

Policy implications

When expectations become de-anchored, inflation can quickly take off and be costly to rein back in. Ultimately, central bank policy credibility and price expectations are difficult to precisely define, and any assessment of anchoring can’t be decided entirely based on relationships in historical data.

Policymakers therefore must walk a fine line between remaining patient in their support for the recovery and being ready to act quickly. Even more importantly, they must establish sound monetary frameworks, including triggers for when they would reduce support for the economy to rein in unwelcome inflation.

These thresholds for action could include early signs of de-anchoring inflation expectations, including forward-looking surveys, unsustainable fiscal and current account balances, or sharp currency swings.

Case studies show that while strong policy action has often tamed inflation and expectations for it, sound and credible central bank communication also played an especially crucial role in anchoring views. Authorities must be alert to triggers for a perfect storm of price risks that could be individually benign but when combined may lead to significantly more rapid increases than predicted in the IMF’s forecasts.

Finally, a key feature of the outlook is that there are significant differences across different economies. Faster inflation in the United States, for example, is projected to help drive the acceleration for advanced economies, though pressures in the euro area and Japan are estimated to remain relatively weak.

![]()