By Rina Bhattacharya, Dmitry Vasilyev, and Mauricio Villafuerte

Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) are at the forefront of digital money adoption, offering valuable lessons for the rest of the world. While El Salvador has made headlines by granting legal tender status to Bitcoin, other LAC countries have made significant strides in the introduction of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) to either enhance financial inclusion and payment systems’ resilience or lower cross-border remittances’ costs, as our recent research shows.

The Bahamas pioneered the introduction of a CBDC with the Sand Dollar in 2020, and the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU) and Jamaica have followed suit. Brazil’s CBDC project is also in the advanced Proof-of-Concept stage, seeking to enhance “asset tokenization” by turning assets, such real estate, stocks, and commodities, into digital representations to facilitate their transfer and increase their liquidity.

Notably, four Latin American countries, Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, and Ecuador ranked in 2022 among the top 20 in global adoption of crypto assets. They seek the benefits that digital assets claim to offer, including protection against uncertain domestic macroeconomic conditions, circumvention of capital controls, improved financial inclusion for unbanked populations, cheaper and faster payments, and stronger competition.

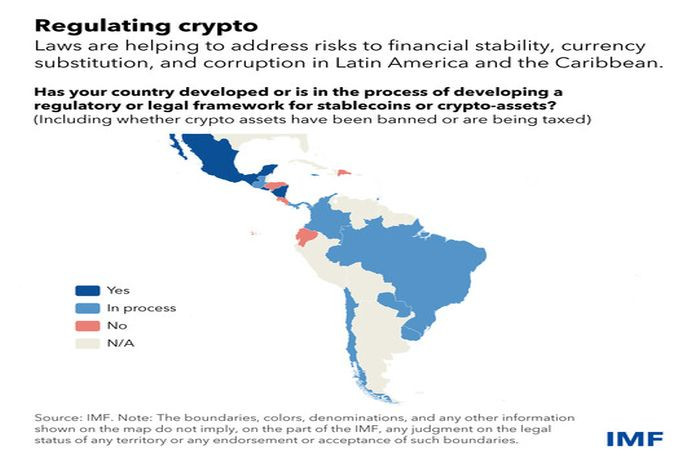

However, crypto asset adoption also presents numerous challenges and risks, particularly for vulnerable LAC countries with a history of macroeconomic instability, low institutional credibility, substantial capital flows, corruption, and extensive informal sectors. Twelve out of nineteen jurisdictions in the region surveyed for our paper in mid-2022 either already have a special regulatory framework in place or are in the process of creating one.

Adopting crypto

Regulation of crypto assets varies across LAC countries. While El Salvador has made Bitcoin legal tender, declared by law to be a valid payment instrument to settle transactions and financial obligations, other countries like Argentina and the Dominican Republic have prohibited the use of crypto assets due to concerns about their impact on financial stability, currency and asset substitution, tax evasion, corruption, and money laundering.

El Salvador’s experience with Bitcoin suggests there are risks to adopting unbacked crypto assets those that rely on supply and demand rather than on any asset for value and that are subject to significant price volatility, even when explicitly supported by the government. A 2022 national survey suggests that Bitcoin is still not a widely accepted medium of exchange in El Salvador, despite its legal tender status and substantial government incentives.

Effective adoption of stablecoins, crypto assets that aim to have a stable price relative to a specified asset can also pose challenges, as demonstrated by Meta’s pilot project. It would have allowed users in the US and Guatemala to make domestic and cross-border payments without fees through its digital wallet, the Novi. While potentially reducing costs of cross-border payments, the project also posed the risk of domestic currency substitution in Guatemala. It was wound down in 2022 amid Western regulatory pushback against Meta’s expansion into cryptocurrencies.

The promise of CBDCs

Most central banks in LAC are analyzing the potential introduction of CBDCs, with some island nations having already issued their own. According to our survey with government officials in the region, half of the respondents were considering both retail (i.e., designed for the general public) and wholesale (i.e., intended for use by financial institutions) CBDC options.

Most survey participants viewed CBDCs as a means to enhance their payment systems and broaden their access. They deemed financial inclusion and monetary sovereignty as crucial factors in favour of retail CBDC issuance by facilitating the integration of unbanked individuals and curbing currency substitution towards stablecoins or crypto assets.

On top of these objectives, the central banks of the ECCU and the Bahamas have issued their own CBDCs to boost financial inclusion for communities in remote islands and to strengthen the resilience of the payments system to natural disasters and pandemics. A slow take-up and disruptions in access to CBDCs in these countries highlight the importance of investing in public awareness and robust infrastructure to promote the adoption of CBDCs.

Managing risks

Crypto assets present risks that vary by country circumstances. The IMF has provided guidance on key elements of an appropriate policy response to mitigate the risks while also harnessing the potential benefits of the technological innovation associated with crypto assets.

If well-designed, CBDCs can strengthen the usability, resilience, and efficiency of payment systems and increase financial inclusion in LAC.

While a few countries have completely banned crypto assets given their risks, this approach may not be effective in the long run. The region should instead focus on addressing the drivers of crypto demand, including citizens’ unmet digital payment needs, and on improving transparency, by recording crypto asset transactions in national statistics.

Rina Bhattacharya is a senior economist, Dmitry Vasilyev is an economist, and Mauricio Villafuerte is a division chief in the IMF’s Western Hemisphere Department.