By Johnny Coomansingh

Unity among panmen, and the creation of a backseat for ‘badjohnism’ were the results of the inauguration of the Trinidad and Tobago (T&T) National Panorama in 1963. Steelpan culture took a new direction; a direction of constant improvement, competitiveness, and a reduction of violence among panmen. Once-upon-a-time, Aldwin Roberts (Lord Kitchener) in his 1963 calypso ‘The Road,’ declared:

“Ah hear how they planning fo’ carnaval coming

Ah hear how they planning fo’ carnaval coming

They say they go beat people and they doh care ‘bout trouble

But tell them doh worry with me,

Is ah different ting–1963 because

The road make to walk on carnaval day

Constable ah doh want to talk but ah got to say

Any steelband man only venture to break this band

Is a long funeral from the Royal Hospital

Ah get information ‘bout the situation

The tell me Tokyo is a danger with Desperadoes

They even call Sun Valley, Trinidad All Stars and Tripoli

They could play they mas

As long they doh tackle me when they pass…”

Gone are the days when steel bands were like warring factions, especially at the place known as Green Corner in Port of Spain. Nowadays, instead of the fighting and bloodshed among panmen, there is another type of war; a war of steelpan music on the big stage in the Queen’s Park Savannah!

In the grand battle among steelpan orchestras (steelbands), the winner of the National Panorama emerges with bragging rights and money. The first prize this year for the large conventional band category is TTD one million. The finals will be staged on February 14, 2026. Steelpan orchestras from all over T&T vie to be the number one band. The National Panorama, part and parcel of steelpan culture, is one thing, but there are covert elements that affect the growth of steelpan culture in T&T.

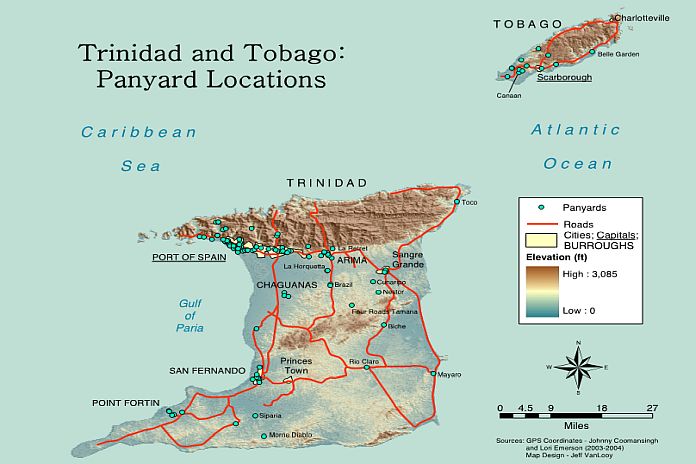

Port of Spain has remained the mecca or the core of steelpan culture. Any map concerned with the steelpan landscape in T&T will illustrate that there is no place on Earth where there is such a preponderance of steelpan orchestras. Part of the history of the steelpan’s emergence are in the hilly villages “behind the bridge” (East Port of Spain). Conflicts associated with rampant violence in these communities did not impede the growth, development, and/or commodification of the steelpan. Nevertheless, in terms of steelpan culture, all is not well in T&T.

It is sad that many rural areas are still not developing a ‘steelpan culture.’ Pan Trinbago, the world governing body for the steelpan attempted to inveigle local communities with the scheduling of steelpan events throughout the country, but without much success. Leadership problems, lack of funding, land tenure issues, rural/urban drift, and capital leakage from such districts stymie, to a large extent, the development of steelpan culture. Pan Trinbago also needs help with their governance of the steelpan phenomenon. Some citizens of T&T were angered with regard to Hydrosteel’s (Whitmyre and Price) patenting of a hydroforming press for stainless steel pans. Others took a neutral stance on the matter. They intimated that everything is in flux.

Concerning the instrument’s commodification, there is proof that the steelpan as a cultural icon of T&T has had substantial exposure in terms of the marketing process via the mass media, and the World Wide Web [WWW]. The steelpan is now in cyberspace, far beyond the promotion of a National Panorama. People can go to the WWW and order a tuned steelpan with a credit card. It is a remarkable development, considering where the instrument emerged. Migration of citizens, especially to North America and Europe from the Caribbean region, has also rapidly increased the rate of distribution of the instrument on the world stage. Tourism has also played its part in the dissemination of the steelpan.

Players of the national instrument and anyone associated with steelpan are now free of the stigma of the waywardness that plagued them for so long. They are no longer considered as societal outcasts. They have sweetly played their way into the hearts and souls of the population, even the Christian church. The label has been peeled off from the steelpan people, but there is a sinister culture of violence that is breeding in stagnated pools of ignorance and arrogance in localities “behind the bridge,” and elsewhere in Port of Spain. It is a battle for territory; turf wars.

Extant in the landscape is a battle for chora, the space that gives a place for being. Today, there are gangs in East Port of Spain fighting for the domination and control of territory. What is the nature of such territory? No one really knows, but maybe it could be related to illicit drug-running activity and long-standing grudges. Trinidad is precariously close to the South American mainland and is well-known to be a transhipment point on the globe for illicit drugs.

The National Panorama and steelpan movement is doing what it could possibly do to stem the tide of violence. Sadly, one of Trinidad’s best-loved steel orchestras Desperadoes, formerly located up on Laventille Hill, East Port of Spain, had to be relocated to George Street, Port of Spain. Crime and safety issues prompted the move. Violence in such areas serves as a deterrent in the growth and development process of the steelpan movement. Pride of place among certain groups is not taking precedence in such areas. Some individuals sacrifice an entire community to serve their selfish and violent goals. Could this be fixed? Rejuvenated?

Conflicts associated with the commodification of the steelpan have been well documented, especially the conflict associated with the patenting of a hydroforming press by two Americans (Whitmyre and Price) to mass manufacture the steelpan. My opinion on this matter is that the Americans should not be blamed for their actions. In my view, consistent with the dynamics involved with the growth/non-growth and development/non-development of steelpan culture in T&T, Whitmyre and Price served as a ‘godsend’ in the sense that they have prevented the decline of the invention and have placed it on the platform of rejuvenation.

Since the curtailment of funding from steelpan research at the University of the West Indies (UWI), at the Caribbean Industrial Research Institute (CARIRI) to be exact, discoveries were emerging in T&T, but at a rate too slow for economic viability. It takes well over 60 hours to manually make a good steelpan. Whitmyre and Price can make thousands in one month.

Deepak Chopra said that we must be able to see the solution to the problem within the problem itself. Stephen Covey said, “The way we see the problem is the problem.” The first reaction by Trinidadians was that the culture was being stolen. Cultural piracy? But since this pan-making event, there was an upsurge, however minute, in the awareness about steelpan culture at every scale, local, regional and international. Not only are Whitmyre and Price involved with the patenting of devices involved with steelpan, but Panyard Inc., of Akron, Ohio, boasts of their Solid Hoop pans with their very own trademark.

Trinis could argue all they want, but it is clear that steelpan is no longer a Trinidadian issue. It is now a global issue with a geographic perspective. Ellie Manette (deceased) the once poor boy from the northern coastal village of Sans Souci, Trinidad, then steelpan maker ‘…under the breadfruit tree’ in Port of Spain, became a permanent professor of music at the University of West Virginia, Morgantown. In an interview with National Public Radio (NPR) this is what Manette said: “For some reason, this small state generates the students that I was looking for. I wanted to pass on my skills…I wanted to create a symphony from steel.”

In the NPR commentary, the narrator said, “The steel drums may have come from the islands of the Caribbean, but many who want to learn to play or build the instrument are travelling to the hills of Appalachia.” Back then in Manette’s steelpan summer workshops, hundreds of students enroll; even citizens from T&T. Illustrative of the cultural reversal, it means that T&T is no longer the sole purveyor of the instrument. Manette’s work facilitates the 500 or so steelpan school programs in the United States. Many of his handmade instruments are now played in the hallowed halls of learning. I had the privilege of presenting my research on the steelpan in Morgantown. Some of these students may very well return to T&T to join in the National Panorama.

Concomitant with its commodification and overarching globalisation, there is enough evidence to conclude that the United States of America (USA) is the pseudo-parent, ‘godparent,’ or stepparent of the instrument. There is enough evidence to show that the USA has been the frontrunner with regard to research and development, manufacture and marketing of the phenomenon. Panyard Inc of Akron, Ohio, has managed to imitate several items relevant to the steelband culture, even some items that Trinidadians have almost forgotten. After looking at their catalog, Panyard Inc. has probably covered all the bases with regard to steelpan culture. The company also provides the public with a steelpan showroom and exhibits the flags of the United States and T&T. I doubt whether such a dynamic showroom exists in T&T.

Discussions surrounding the sorry state of the art form in rural localities in T&T are enough to deduce that something is malfunctioning in the system. There is abundant evidence to prove that there has to be governmental or quasi-governmental intervention if steelpan culture is to blossom in such communities. A prolific steelpan community in rural areas would certainly give a boost to their local economies. In terms of development via tourism, steelpan as a cultural product could be marketed in rural communities; steelpan music is a great attraction.

Despite the passivity in many sectors, there are those who are excited about the steelpan. They are the people who congregate in the panyard and worship in the pantent. The panyard has replaced the church and the settlement house (houseyard) for some segments of the Trinidadian society. Then there are ‘disciples,’ the faithful followers and supporters seen and unseen, who venerate their pansides (steelpan orchestras), especially during the National Panorama. There are those who physically accompany their orchestra regardless of success or failure, through hard times and good times, by night and by day. There are those who support steel orchestras today at home and abroad only through the eyes of televised programs at the local, regional and international scale.

Although the National Panorama fosters unity and clean competitiveness, there is a bone of contention that insidiously undermines the growth and development of the instrument in T&T. There are people, religious and otherwise, in Trinidad, who do not accept the instrument as the national instrument. Until such time, when absolute acceptance of the instrument is no longer an issue, we are still grateful for the unity the instrument proffers and certainly the backseat for badjohnism.