By Esha Zaveri, Richard Damania, and Saroj Kumar Jha

Throughout history, water has been the quiet engine behind progress: farmers irrigate fields to grow crops; industry needs it to produce goods and generate energy; and people, communities and cities draw on it for drinking, sanitation, and public health. Technology also made it possible to reach deeper aquifers and more distant rivers, expanding water use and exposing fundamental tensions in how water is valued and distributed, and who bears the costs.

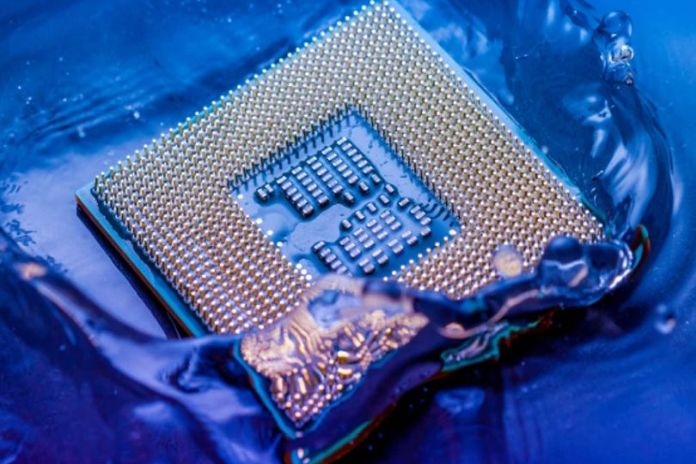

Artificial intelligence (AI) could add a new dimension to these old tensions. Generative AI systems, like large language models, depend on cloud infrastructure underpinned by data centers that house thousands of servers running non-stop. Today, these facilities account for about 1.5 percent of global electricity consumption, and most capacity is concentrated in just a few markets. But with the rapidly growing demand and investment, data center electricity use could more than double by 2030 to 945 terawatt-hours (TWh)—about the same amount used by Japan every year.

With hunger comes thirst

Data centers are not just energy-hungry. They are also thirsty. Computing generates enormous amounts of heat, and much like our bodies cool themselves by sweating, data centers use water evaporation to keep servers from overheating, often using potable water from the same supplies that serve communities, homes and businesses. Data centers also indirectly contribute to water use through the electricity generation needed to power them. This indirect use can make up 80% or more of their overall water use. Taken together, one estimate suggests that global AI-related water demand could reach 4.2 to 6.6 billion cubic meters in 2027, equivalent to four to six times Denmark’s annual water withdrawals.

Getting a precise picture of data center water and electricity use remains a Sisyphean task: reporting is patchy, and the goalposts keep shifting as AI adoption and efficiency evolve. But these projections offer a valuable, if imperfect, guide to where demand is headed.

Global picture, local reality

Globally, the amount of water used by data centers is small when compared with other uses, such as for agriculture. However, locally, the demands posed by concentrated clusters of data centers could compete with other needs, fueling concerns about the adequacy of water resources. This is especially critical for developing economies that are keen to invest in and build AI-related infrastructure.

Warmer climates tend to make cooling more water-intensive, while seasonal cooling demands often surge just as other water uses peak. In water-scarce areas, the indirect use of water in electricity production can strain rivers, aquifers, and ecosystems. As AI turbocharges investments in data centers in developing economies amid increasing water stress, where these centers are built and how water is managed locally could prove decisive.

All this is unfolding as water deficits are becoming the new normal. In just the past two decades, global freshwater reserves have fallen by an average of 324 billion cubic meters per year, a loss equal to the combined annual flow of Western Europe’s largest rivers. These trends are especially challenging in lower income countries where over the last half-century, periods of severe rain shortfall and droughts have increased by 233 percent, creating major headwinds for economic growth.

Getting it right

Already over a third of data center infrastructure is concentrated in areas grappling with water scarcity, namely places where annual net water withdrawals exceed available water (see red bar in figure).

This is striking, but it is not surprising. Companies have few incentives to factor water into their decisions. Many water-scarce economies turn out to be among the most water-intensive because water, while priceless, is notoriously undervalued. When water is supplied cheaply or even freely, it is used liberally, creating an illusion of abundance even in arid regions. This may help explain why decisions about where to build data centers prioritize easily measurable costs like electricity and reliable broadband access while overlooking water and the functions of environmental assets like watersheds that resist simple valuation. Governments also compete to attract data centers and computing facilities through subsidies and tax incentives, often without assessing long-term implications for local water security.

In such contexts, the arrival of a new concentration of industrial users could inadvertently tip the local water balance, forcing us to confront old questions about how best to price, protect, and allocate water. This tension hits hardest in the “middle-readiness” economies, where digital infrastructure is expanding rapidly, AI capabilities are just emerging, but water governance may be weak and unable to keep up with new demands. To confront these risks, countries need watershed-informed siting, transparent monitoring and disclosure of industrial water use, innovations in cooling, recycling and reuse, and incentives that reward conservation while balancing competing demands from agriculture, industry, and communities.

At the same time, the technology that is driving new demand for water also holds the promise to manage water more wisely. AI tools could help detect leaks in city pipes, fine-tune irrigation schedules, forecast floods and droughts, and optimise water reuse. In economic terms, the marginal social benefit of these applications could potentially exceed the marginal social cost of the water AI uses. But whether AI lands on the right side of the water ledger will depend on the choices we make.

As the cloud meets a thirsty world, the question is whether its promise will blind us to the watersheds that sustain us or finally help us steward them with greater care.