By Viviana Perego, Elena Mora Lopez, Emiliano Magrini and Valentina Pernechele

During a visit to El Salvador, we met María Alexandra Tamanique, a maize farmer in La Libertad. She told us about the difficult decision she had to make during the fertilizer price increase in 2022–2023: to reduce fertilizer use and accept lower crop yields. “My maize yields fell sharply,” she told us, as poor road conditions and high transportation costs made it difficult to access mills further away.

Her experience is common across Central America and the Dominican Republic: when global prices move, small producers often feel the effects late and only partially, as many intermediaries stand between their farms and final buyers.

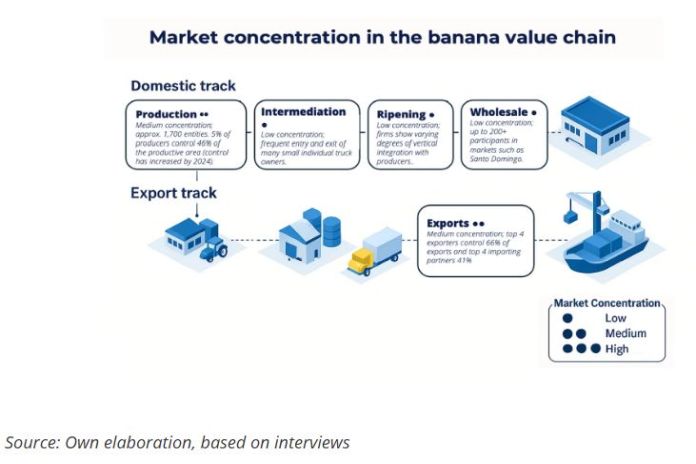

Work completed in 2024 found that only a fraction of world price movements is passed through to domestic prices, underscoring the central role of domestic market dynamics in shaping local prices and volatility. Building on that evidence, our new report examines where costs, risks, and logistics delays concentrate in El Salvador’s white maize and the Dominican Republic’s banana value chains (both pillars of local diets but that move through very different market structures), and which practical measures can make markets work better for households and producers.

From farm to table: why the structure of food markets matters for what consumers pay.

In El Salvador, maize runs on two tracks. Domestically produced grain—grown by hundreds of thousands of smallholders—moves through informal intermediation into urban wholesale markets, with prices set day-to-day by local supply, demand, and basic quality screens. Imported grain, by contrast, is procured by a concentrated agro-processing segment, often via forward contracts, and flows through formal wholesalers and supermarkets.

First-mile services such as hauling, drying, and grading are often thin and uncoordinated, and trusted verification of quality is scarce. Because transactions are loosely organized—who buys from whom, how quality is checked, and how quickly money is paid—local prices can diverge from international benchmarks, and farmers face wide price dispersion for similar grain. These frictions lengthen the cash cycle and make it hard for local maize to enter formal processing on clear terms.

In the Dominican Republic, bananas also follow dual mechanisms. Fruit destined for the international market is priced through annual contracts benchmarked to certified quality and sustainability standards; fruit destined for the domestic market moves via fragmented intermediation, with prices driven by daily conditions and limited differentiation by production practices.

Gustavo Gandini, technical lead of BANELINO (Asociación de Bananos Ecológicos de la Línea Noroeste), pointed out that, despite having fruit, this year the volumes under contract were lower, which, added to a suspended route, affected extra orders that did not always find space in refrigerated ships or containers and determined access to buyers.

In practice, logistics—vessel slots, reefer availability, inspection cadence, documentation—determine whether fruit reaches buyers and at what claim rate. Evolving private standards increase fixed costs; without coordinated audits and recognised labs, small producers pay more per unit than larger firms to meet the same bar.

How can public policies improve market efficiency?

In recent years, governments in the region have relied mainly on emergency measures—such as temporary tariff relief, safety-net expansion, and targeted food assistance—to cushion food price inflation. These tools remain essential in crises, but they do little to change how maize or bananas move from farm to market. Our analysis points to a complementary agenda that focuses on market-enabling public goods, rules, and services. This agenda aligns with the World Bank Group’s new AgriConnect initiative, which aims to transform smallholder farming, create jobs, and strengthen food security by improving infrastructure, policies, and private investment along value chains.

What to do now, next, and later.

- In the near term, make information and processes trustworthy: publish moisture-adjusted maize prices and buyer specifications, and measure and document quality at the first sale point so farmers have an incentive to invest in drying and storage and buyers can pay with confidence; move to e-documents and appointment systems at ports, and use risk-based inspections so compliant firms move faster and clearing times for perishable exports drop.

- Over the medium term, help producer groups and buyers work together to bundle drying, grading, testing, and hauling at lower cost, and expand insurance services so bad weather or price swings don’t force distress sales.

- Over the long term, plan with market realities in mind: for maize, pair open imports with domestic aggregation, quality verification, and working-capital tools so local grain competes on clear terms. For bananas, match productivity gains with cold-chain and compliance with standards to ensure product is consistently ship-ready.

Ultimately, making markets work better is about a package of measures, not a single fix. When quality is clear from the start, prices and procedures are predictable, logistics and cold chains function reliably, and risk-management tools are in place, markets become more resilient and inclusive, and producers like María Alexandra and Gustavo can plan their crops better, improve their incomes, and even help generate jobs in their communities.

![]()