With rising life expectancy and plummeting birthrates, Taiwan is poised to undergo a stunning demographic transformation. The United Nations has estimated that the share of the population aged 65 and above in Taiwan will increase from 15 percent in 2019 to 35 percent in 2050, making it one of the oldest countries in the world (trailing only South Korea at 38 percent, and Japan at 37 percent).

As a result of the island nation’s aging populace, economic growth prospects are likely to be stunted, as savings, private consumption, investment, and overall labor availability are expected to decline. Although the government debt-to-GDP ratio is relatively low by international standards (25 percent in 2023, according to the International Monetary Fund [IMF]), the government’s debt could become unsustainable in the future due to the large financial burden of supporting the elderly. More importantly, the slow economy – accompanied by the potentially colossal expense of elderly care – could call Taiwan’s ability to fund a strong military into question.

Explaining Taiwan’s rapidly aging population

Taiwan’s challenging demography is a consequence of a combination of decreasing birth rates and increasing life expectancy over the past few decades. Taiwan’s total fertility rate (TFR) declined from nearly four live births per woman in 1971 to only one in 2021. During the same period, average life expectancy in Taiwan increased from 69 to 81 years, according to data from the United Nations.

The diminishing youth population has been at least partially caused by government policies intended to slow population growth. After World War Two, rapid population growth was widely considered a hindrance to economic development. Therefore, each family was encouraged to have only two children. However, economic development allowed for improved public health measures and medical advances, which in turn contributed to decreasing mortality rates and increased longevity. Over the last decade, the rising cost of living and stagnant wages have further discouraged many Taiwanese from marrying or having children. Additionally, a growing percentage of the younger generation has opted to prioritize career development over family life.

How bad is it?

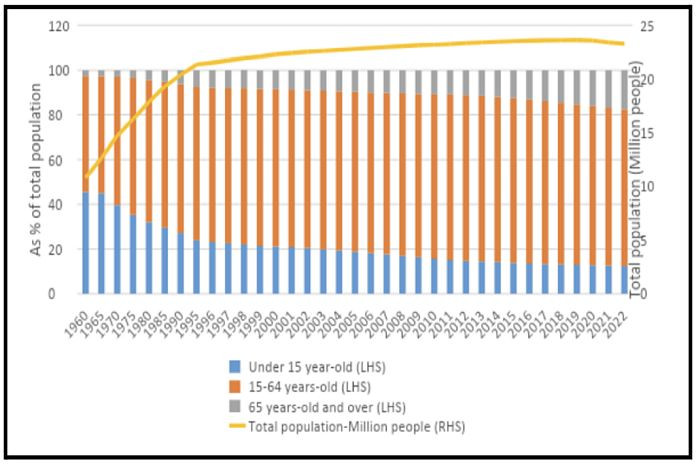

Taiwan’s official statistics have showed that the share of the population under 15 years old, which accounted for 45 percent of the total population in 1960, has dwindled sharply to only 12 percent in 2022. During the same period, people aged 65 and above increased from a 3 percent to 18 percent share of the population. The share of working population aged.

The declining working population has contributed to the mounting labor shortage. Taiwan’s National Development Council (NDC, 國家發展委員會) has estimated that the country will start to lose the “demographic dividend” (a situation in which there is a greater number of working-age adults than dependents) in 2028. As a consequence of the decreasing working population, the dependency ratio (measured by the number of people aged 65 and over per 100 people, as contrasted with the number aged between 20-64) is expected to increase. The government has estimated that in 2040, every two Taiwanese people aged between 15 and 64 years will have to take care of one elderly person aged 65 and above – a significantly heavier burden compared to 2022 (when there were four young Taiwanese to each elderly person).

Counterbalancing the negative impacts of an aging population

The government has been pursuing several strategies to ease the demographic crunch. For example, it has introduced various pro-natal measures, such as financial assistance for dependent children, special tax rebates, paid maternity leave, and other policies. The Gender Equality of Employment Law, enacted in 2002 and amended in 2022, aimed to prevent discrimination against married and pregnant female workers. Additionally, in 2008, the Ministry of the Interior (MOI, 內政部) introduced further steps to encourage firms and businesses to adopt family-friendly workplace practices and create child-safe environments.

To date, policies aimed at increasing TFR have not been effective. Instead, Taiwan’s TFR has continued to drop, falling from 1.73 children per woman in 1992 to 1.27 in 2012 and 0.87 in 2022. Even if the TFR were successfully boosted, it could take at least two decades for an increased birthrate to translate into additional available labor for the economy. Hence, the long-term policy to increase TFR might not be able to cure the potential economic slowdown that would be caused by the labor shortage in the years to come.

Apart from boosting TFR, several measures could be helpful to counterbalance the potential impact of a shrinking working population on the economy. The first of these would be to increase labor productivity. Since the economically active population will continue to age and decrease in number, labor productivity must be enhanced in order to maintain a decent level of economic growth. Taiwan’s labor productivity in 2021 (measured by GDP per hour worked) is USD $53.14, lower than most of the advanced economies of Europe and North America.

However, the labor productivity measured by output per hour worked may not be particularly accurate. In the case of Taiwan, laborers’ wages have been depressed for many years. The island has potentially produced a similar value of goods and services as other advanced countries, but the understated wages have weighed down measurements of production value. As such, raising wage levels in parallel with labor productivity will be key.

Second would be the quantitative expansion of the labor force by encouraging the greater participation of women, the elderly, and youth. In 2021, Taiwan’s labor participation rate was 59 percent, lower than South Korea, Japan, and the United States (see Table 1). This deficit is particularly pronounced among the young population aged between 15 and 24 years.

The labor participation rate among the middle-aged population is higher in Taiwan, but it clearly declines after age 50. While 26 percent to 36 percent of people aged 65 and above in Japan and South Korea remain active in the labor force, the same age group in Taiwan accounts for only 9.2 percent.

Additionally, according to the NDC, Taiwan’s female labor participation rate (52 percent) is also considerably lower than the rate for males (67 percent). The wage disparity has likely discouraged women from participating in the workforce, as the female hourly wage was only 84 percent of the male wage in 2022.

Beyond domestic laborers, foreign workers could be an immediate solution to Taiwan’s declining labor force. As of the end of September 2022, there were roughly 78,000 foreign immigrants in Taiwan, including foreign workers and spouses. However, foreign immigrants accounted for only 3.4 percent of Taiwan’s total population, which is lower than many advanced economies, such as France (13 percent), Singapore (43 percent), Thailand (5.2 percent), Malaysia (10.7 percent), all of whom have also suffered from low TFR in recent years.

Nevertheless, while encouraging immigration could quickly fill the labor shortage, it may not be a long-term solution given that immigrants would also age. In addition, the many social integration and national identity issues linked to immigration could prove controversial and politically contentious in Taiwan.

Challenges beyond economic growth

An aging demography is a general phenomenon that many developed countries have been experiencing in recent years. However, statistics compiled by the United Nations have showed that the aging population in Taiwan, together with Japan and South Korea, could be a particularly serious concern in the next decade.

For Taiwan, an aging populace not only poses challenges to economic growth, but could also increase uncertainty about how the island will be able to finance its national security needs in the face of the growing military threat from China. Taiwan’s military expenditure as a percentage of GDP in 2023 was 2.4 percent, higher than the regional average in 2021 of 1.7 percent. However, the higher percentage does not necessarily translate to increased military might. With Taiwan’s limited growth potential, the smaller GDP means less economic resources could be devoted to strengthening the military in absolute terms, despite the high percentage of military expenditure in GDP.

The most daunting task for Taiwan will therefore be to seek new approaches to sustain moderate economic growth, as well as effective policies to slow down the impacts of its aging population in the near future. Taiwan’s consistently low TFR has proven that previous policy measures (such as financial support and expanded maternity leave) have not been effective. There is a need for a comprehensive economic development policy, which should also include measures such as more flexible employment and working days for married couples, affordable public housing, and promotion of gender equality, as well as the construction of a friendly environment for childbearing.

Socioeconomic structures might also need to be adjusted to allow for greater inclusion of young, elderly, female, and foreign workers, as well as greater investment in boosting overall productivity. Such bold and extensive initiatives will need a strong and reliable government to maintain public consent for such a change.

The main point: Taiwan’s aging population not only poses challenges to its future economic growth, but also for its capability to finance its military development. A set of bold and comprehensive policy measures is in urgent need to address the daunting tasks linked to Taiwan’s aging population.