By Dr Mohamed Z M Aazim, Adviser, Debt Management Unit, Commonwealth Secretariat

The general government debt (GGD) – which includes what the state and state-owned enterprises owe – of Commonwealth countries declined in 2021 and 2022, as a share of combined gross domestic product (GDP), meaning they owed less debt compared to the size of their economy.

However, in 2023, this debt share started going up again, and it’s getting close to the size of their economies. This is certainly not a good sign.

This situation is putting governments in a tough spot, leaving them with limited options to make the right decisions to reduce their debt burdens. For Commonwealth countries that are currently in debt distress, meaning they can’t make timely payments on their debts or have already defaulted, there’s an urgent need for a well-structured plan to get their debt back to manageable levels.

Why does this matter so much? If we fail to take coordinated action now, the consequences could be severe, and it’s the citizens who will ultimately bear the brunt. High debt levels make it incredibly difficult for governments to continue to meet the costs of health, education, and other basic needs of their populations because of the constraint of debt servicing.

A closer look at the numbers

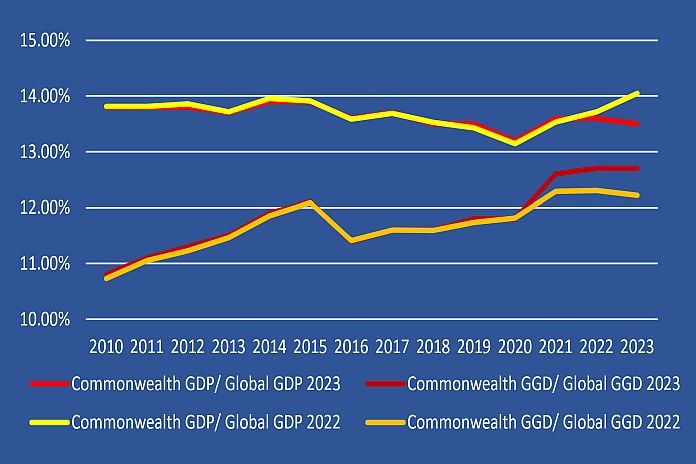

The Commonwealth, representing 56 countries, make up a significant portion of the global economy, contributing about 13 to 14 percent of the world’s total economic output from 2010 to 2023. During this period, their combined GGD made up 11 to 12 percent of the world’s total.

It’s worth mentioning that between 2020 and 2023, while the Commonwealth’s share in the global economy has been shrinking, the amount of GGD held by its member countries has been increasing. As shown in Figure 1, this trend became more evident after the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in 2023.

In 2023, the clear convergence of the combined GDP and GGD in Commonwealth countries is making debt vulnerabilities more pronounced. This is also happening globally.

Unpacking the causes

The increase in debt is happening because it is costing more to pay off the existing debt, both in advanced and developing countries. Many governments have been spending more to boost their economies and respond to rising food and energy prices as they phase out pandemic-related financial support.

Developing countries, still grappling with debt burdens, are also facing higher interest rates and a strong US dollar, which undermines their economic and financial stability. This, in turn, hampers the ability of those governments to fund development goals, both through available scarce resources and market access, aimed at supporting their populations.

Furthermore, the projected economic growth rate of 3 percent in 2023 and 2.9 percent in 2024 – which are well below the historical average of 3.8 per cent from 2000 to 2019 – will make it even more challenging for governments to meet their debt obligations.

Policy considerations

These developments demand the full attention of policymakers, especially those in Commonwealth developing countries. They should accelerate efforts to reduce debt vulnerabilities and reverse the long-term trend of increasing debt.

To address GGD vulnerabilities, policymakers need to adopt a credible public financial management framework, which helps balance spending needs with debt management priorities, in line with medium-term debt strategies.

For low-income Commonwealth countries, it’s equally important to address revenue gaps and identify additional income sources. Many Commonwealth countries are dealing with public debt levels that are either unsustainable or close to debt distress. To tackle this, they need to return to fiscal consolidation policies to reduce their deficits and the total debt they owe by implementing measures, such as enhancing their revenues, introducing cost-reflective pricing for food and energy, and cutting down on wasteful spending.

In cases where Commonwealth countries already have high levels of public debt and face challenges in accessing the financial markets, a comprehensive methodology, involving fiscal discipline, debt reprofiling and, where feasible, debt restructuring, is necessary.

A few Commonwealth countries already taking steps in this direction, going beyond multilateral mechanisms for forgiving and restructuring sovereign debt. They are experimenting with comprehensive mechanisms for debt restructuring, working with their complex and diverse creditors. This approach involves good faith negotiation with several external and domestic creditors, focusing on a comprehensive debt treatment in line with the parameters set by multilateral financial institutions, debt sustainability targets and the principle of comparability of treatment.

Taking action on the rising debt-to-GDP ratios is crucial now. The future of development in Commonwealth countries greatly depends on prudent public debt management, which can create fiscal space to absorb external shocks, attract new investment and finance development goals, ensuring that no one is left behind.