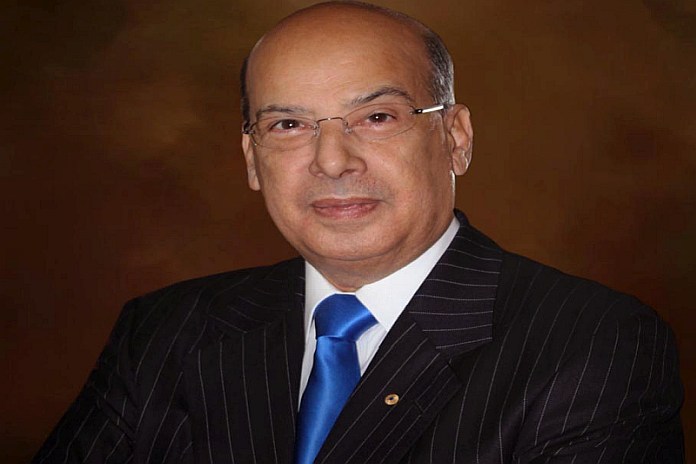

By Sir Ronald Sanders

The public health and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has rightly focused the attention and resources of governments around the world on suppressing and containing it.

The cause has been made more costly and more prolonged by those who resist inoculating themselves against a disease that has officially infected 227 million people worldwide, killing 4.7 million of them. Estimates of underreporting in many regions put the death rate, more realistically, at 7 million.

While governments – particularly those in small countries with scarce human and financial resources – have been concentrating on getting out of the trap of the COVID-19 pandemic, the persistent and pervasive threat of Climate Change has been growing alarmingly.

The entire world is now faced with the troubling prospects of long periods of extreme heat; prolonged periods of drought followed by devastating floods and overflowing rivers; severely reduced agricultural production, leading to food shortages; increase in vector-borne diseases such as dengue fever; grave water shortages; and hugely increased costs of energy.

All this will impact businesses of all kinds, causing closures, unemployment, poverty expansion and greater hordes of refugees and migration than we have seen so far.

A new study, conducted by the prestigious, Royal Institute of International Affairs (RIIA) in London, paints a grim picture of the prospects for the next 30 years, unless greenhouse gas (CO2) emissions are significantly reduced by the world’s biggest polluters. These include the United States, China, India, the European Union and Canada.

The figures, produced by authoritative research. reveal that global efforts to reduce CO2 emissions are dangerously off track.

One of the troubling observations is that, while in 2019, a potential 300 billion working hours were lost due to temperature increases globally, 52 percent more than in 2000, COVID-19 resulted in around 580 billion lost working hours in 2020. Therefore, “temperature increases are already resulting in the equivalent of over 50 percent of COVID-19-induced lost working hours”.

Worryingly, the report concludes that if emissions follow the trajectory set by the reduction commitments made by countries, there is less than one percent chance of reaching the 1.5°C Paris Agreement target.

Caribbean islands and continental countries, such as Belize and Guyana, with low-lying coasts would feel the full brunt of this pending disaster. Here are some of the findings in the report.

Death by heatwaves

Globally, heat-related mortality has increased by nearly 54 percent in persons over-65 in the past two decades, reaching 296,000 deaths in 2018. If emissions do not come down drastically before 2030, then by 2040, 3.9 billion people are likely to experience major heatwaves.

Insecurity by food depletion

In recent years, regional drought and heatwaves have caused 20 to 50 percent crop harvest losses. The global food crisis of 2007–08, led to a doubling of global food prices, export bans, food insecurity for importers, social unrest, and mass protests in many countries.

Death and destruction by floods

By 2040, almost 700 million people each year will likely be exposed to prolonged severe droughts of at least six months’ duration. One billion people now occupy land less than 10 metres above current high tide lines. In 2020 there were 23 percent more floods than the annual average of 163 events in 2000–19, and 18 per cent more flood deaths than the annual average of 5,233 deaths.

Vector diseases increase

Experts are concerned that climate change is likely to increase the prevalence of emerging infectious diseases and vector-borne diseases.

They argue that Climate Change disrupts ecosystems and increases the risk of diseases jumping to new hosts. Scientists have been warning for many years of the probability of pandemics increasing as a result of climate change.

In 2008, a study published in the journal, Nature, found that over the previous decade nearly one-third of emerging infectious diseases were vector-borne, with the jumps to humans corresponding to changes in the climate. For instance, insects such as infection-bearing mosquitoes follow changing geographic temperature patterns. Nine of the ten most suitable years for the transmission of dengue fever have occurred since 2000.

Interconnected crises

According to the RIIA report, interconnections between shifting weather patterns, resulting in changes to ecosystems, and the rise of pests and diseases, combined with heatwaves and drought, will likely drive unprecedented crop failure, food insecurity and migration of people.

All this, the report argues, could result in the potential breakdown of governance and political systems as societies become increasingly unstable due to lack of income as well as competition over limited food supplies.

The report says that experts are concerned that such situations could lead to a rise of extremist groups, paramilitary intervention, organized violence, and conflict between people and states.

Vulnerable States must stand united

Caribbean governments have to remain focused on the clear and present danger of the COVID-19 pandemic that is strangling their countries, but no resident of the region should take their eye off the pendulum that is swinging the dangerous Climate Change wrecking ball.

At the COP 26 UN Climate Change Conference, in Glasgow at the end of October, representatives of vulnerable countries – in Africa, Asia, the Pacific and Latin America and the Caribbean – must make it clear to the governments of highly emitting countries that their profligacy must not continue. If – and only if – these vulnerable countries have the courage to stand together, using their collective leverage, do they have a chance of causing the urgent change necessary to the policies and practices of the big polluters.

The alarm bell has been rung in the RIIA’s expert report, and it sounds a death knell for small states. It should be heeded.