By Tobias Adrian, Gita Gopinath, Ceyla Pazarbasioglu

In a continuous effort to help countries manage volatile cross-border capital flows, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has taken a major step toward a new analytical macroeconomic framework that can guide appropriate policy responses. The work reflects evolving thinking on macroeconomic policy and will feed into the upcoming review of the IMF’s Institutional View on the Liberalization and Management of Capital Flows, which currently guides the Fund’s advice and assessments of members’ policies.

International capital flows provide significant benefits for economic development but can also generate or amplify shocks. This dilemma has long posed challenges for policymakers in many open economies

While flexible exchange rates can act as a useful shock absorber in the face of capital flow volatility, this mechanism does not always offer sufficient insulation, in particular when access to global capital markets is interrupted or market depth is limited.

Diverse approaches

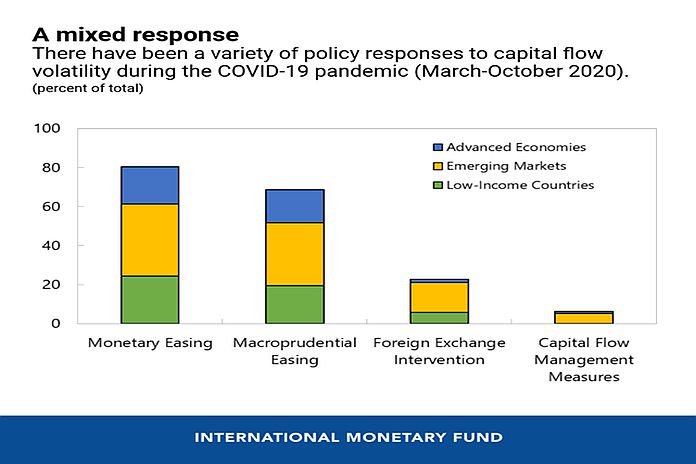

Many policymakers reach for a mix of policy tools to complement interest rate policy when dealing with capital flows. These tools include macroprudential measures, foreign exchange intervention, and capital flow management measures.

Such diverse approaches were also used during the COVID-19 crisis, with significant differences in responses between countries.

Despite the widespread use of the various tools, to date, there has been no clear conceptual framework to guide the integrated usage of these tools.

Multiple tools for stability

A new paper, “Toward an Integrated Policy Framework (IPF),” starts filling the gap. It brings together insights from new models, as well as empirical work and case studies and lays out a coherent framework for the use of multiple tools to achieve macroeconomic and financial stability.

Our analysis suggests that there is no “one-size-fits-all” response to capital flow volatility, nor is it a case of “anything goes” or that all policies are equally effective. Optimal policies depend on the nature of shocks and country characteristics. For instance, the appropriate policy response in a country with less developed financial markets and large foreign currency debts may differ from that of a country that does not have foreign currency mismatches on their balance sheets, or those that can rely on more sophisticated (deep and liquid) markets.

Generally, in countries with flexible exchange rates, deep markets, and continuous market access, full exchange rate adjustment to shocks remains appropriate. However, when a country has certain vulnerabilities, such as shallow markets, dollarization, or poorly anchored inflation expectations, while flexible exchange rates continue to provide significant benefits, other tools can play a useful role as well. In particular, macroprudential measures, foreign exchange intervention, and capital flow management measures can enhance monetary policy autonomy so monetary policy can adequately focus on containing inflation and promoting stable economic growth. The same tools—including precautionary capital flow management measures on capital inflows, applied before shocks hit can also help lower financial stability risks.

Our findings do not rationalize indiscriminate use of tools. In particular, IPF tools should not be used to maintain an over-or undervalued exchange rate. Also, while IPF tools help cope with shocks, most of the time they cannot fully offset underlying vulnerabilities. Thus, they are no substitute for deep markets, healthy balance sheets, and strong institutions. Efforts to promote the development of markets and institutions remain important to complement sound macroeconomic policies.

Additional steps needed

The new framework represents a significant advance in thinking about when various tools should and should not be used and how these tools can work together to achieve better outcomes. IMF staff is focusing on several areas to complete the analysis:

Long-term impacts. The benefits of IPF tools need to be balanced against possible costs such as slower market development and increased risk-taking. Protracted reliance on some of the tools might perpetuate the very vulnerabilities that rationalize their use. For example, persistent interventions might feed a (false) sense of security about future exchange rate developments that leads firms or households to take on more foreign currency debt, thus increasing balance sheet vulnerabilities.

Fiscal aspects. The fiscal stance and public debt levels matter for countries’ vulnerability to shocks, even as fiscal policy itself tends to be less suitable than IPF tools for managing capital flows. The models will be further extended to examine more closely the interaction between different fiscal policies and IPF tools.

Multilateral considerations. A country’s optimal policy mix also depends on the actions of other countries and global institutions. Use of IPF tools may have positive spillovers, especially if they improve macroeconomic and financial stability, and facilitate trade. But there may also be negative spillovers. For instance, capital flow management measures may deflect capital flows to other countries, where such flows may contribute to currency overvaluation and overheating.

Safeguards and metrics. In the IPF framework, the tools are aimed at well-defined macroeconomic and financial stability objectives. In practice, however, tools might be misused and support under/overvalued exchange rates, substitute for warranted macroeconomic adjustment, or impede price discovery and competition. Differentiating between appropriate and inappropriate deployment of IPF tools will require developing suitable metrics for assessing their use.

Work in each of these areas will advance in the period ahead and should result in improved policy guidance for countries facing volatile capital flows.

![]()