Despite a year of unbridled state repression, including massacres committed against supporters of former Bolivian President Evo Morales, who was deposed just weeks after being declared the victor in the country’s October 2019 election, the left-wing Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) secured a resounding victory on October 18 for candidate Luis Arce, Morales’s former finance minister.

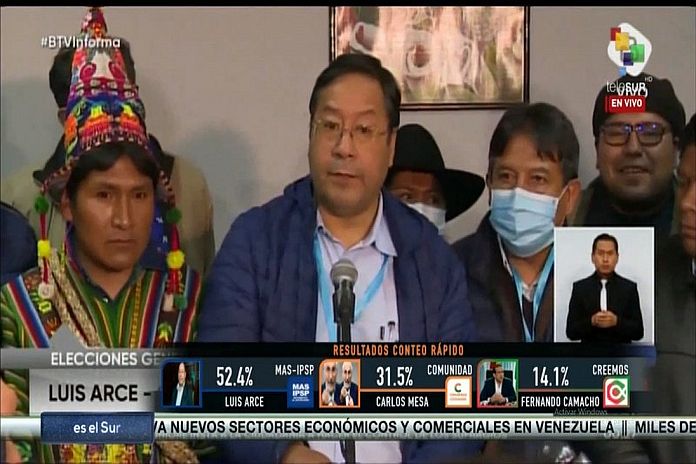

MAS won by such a wide margin that it even surprised many of its supporters in Bolivia and around the world. According to official exit polls, Arce and his vice-presidential candidate David Choquehuanca won 52.4 percent of the vote compared to centre-right candidate Carlos Mesa, who garnered only 31.5 percent.

In order to win in the first round, a candidate must secure more than 40 percent and a margin of at least 10 percent over the nearest rival to avoid a second round runoff. Arce won by an astonishing 20 percent.

Winning the presidential election under the shadow of a US-backed right-wing coup (supported by Canada), was made all the more remarkable by MAS winning a majority in both houses of the Bolivian parliament, This was a veritable left-wing landslide. The majority Indigenous and poor defeated the white, upper-class candidates all down the line. It was one of the most courageous chapters in recent Latin American history.

Even de facto coup president Jeanine Añez conceded defeat through her Twitter account at about midnight.

“We do not yet have an official count, but from the data we have, Arce and Choquehuanca have won the election,” she said. “I congratulate the winners and ask them to govern with Bolivia and democracy in mind.”

Significantly, it was Morales who broadcast the first official victory speech from exile in Argentina.

“Brothers of Bolivia in the world, Lucho [Arce] will be our president,” he proclaimed. “For our country, for the path of economic, political and social development and especially it will contribute to economic growth. From a distance I want to send my brothers Lucho and David my sincerest congratulations.”

This was followed by a speech from president-elect Arce. “We want to thank the Bolivian people […] we thank all for their militancy. We have taken important steps, we have recovered democracy and hope,” he said. Arce also reiterated his commitment to fulfill MAS’s campaign promises. “Our commitment is to work, to carry out our program. We are going to govern for all Bolivians. We are going to build the unity of our country,” he added. “We are going to recover the country’s economy. We have the obligation to redirect our process of change without hatred, learning and overcoming our mistakes.”

Challenges

This victory was a proverbial slap in the face to the United States and its allies, including Canada, who backed the coup in 2019.

Morales’s initial electoral victory in 2005 was a game-changer of historic proportions for Latin America. For the first time in its history, the Indigenous majority had one of their own as president. What’s more, he was a socialist committed to wealth redistribution, helping the country’s poor majority, and nationalizing key industries to take back the nation’s wealth from unaccountable multinational corporations.

This October 18 victory has reaffirmed the strength, political consciousness and courage of the majority poor and Indigenous population of Bolivia, even more than Morales’s initial rise to power more than 15 years ago. The election of December 2005 was fought in a relatively calm environment, while the October 2020 vote took place against a backdrop of ongoing unrest after the chaos unleashed by the year-long interim government.

The objective of the coup was to suppress the majority and cleanse it of Indigenous values and pride, with violence when necessary. However, Bolivians resisted for a full year, strengthening their resolve, as well as their social and political organizations. The October 18 elections proved to be a de facto year-long electoral campaign for the MAS party.

Nevertheless, the conciliatory tone expressed by Arce and Morales was strategic. MAS won the elections, but there are challenges ahead. One is likely to come from the racist, militarized state that organized the coup and tried to intimidate voters during the latest trip to the polls. This military apparatus is still very much in place.

In addition to the challenge of maintaining political power, but linked to it, is the question of control over Bolivia’s lithium resources to which many observers say the coup was linked in the first place. Who can forget the infamous tweet by billionaire Elon Musk, whose Tesla firm relies on lithium, “We will coup whoever we want!”

The process of privatizing the substantial Bolivian lithium reserves, which were nationalized by Morales, is already in motion. How will the multinationals react to the socialist victory in Bolivia? What will the new MAS government do to reverse the measures enacted by the interim regime of Añez?

Geopolitical considerations

The post-election geopolitical considerations for entire hemisphere are immense. Bolivia’s re-entry into the socialist camp may inspire Venezuelans in the upcoming December 6 National Assembly election. Elsewhere, Ecuadorians are set to go to the polls on February 7, 2021, where Lenín Moreno’s increasingly unpopular government has barred former president Rafael Correa from running.

What’s more, Venezuela’s self-declared interim president and opposition leader Juan Guaidó is seeing his international support deteriorate. As I reported for Canadian Dimension in August, a recent press statement issued by the US State Department and Global Affairs Canada featured a dwindling number of ally countries that are now “committed to the restoration of democracy in Venezuela.” This is a far cry from the formerly extensive coalition of dozens of states that have heretofore unequivocally recognized and supported Guaidó. The State Department could not even get sign-on from all of the members of the Lima Group—the multilateral body consisting of 14 countries, including Canada, that is dedicated to a “peaceful exit to the ongoing crisis in Venezuela.”

The story does not end there. Bolivia became a member of the Lima Group after the coup last year. Now the tables have turned and it seems safe to say that Bolivia will withdraw from the multilateral body once the new president is sworn in. Argentina is also caught up in a controversy over its role in supporting regime change in Venezuela. Earlier this month, its centre-left government ordered its representative at the United Nations Human Rights Council to vote against Venezuela. In an act of protest, the Argentinian ambassador to Russia resigned. Will the Bolivian election result move Argentina to withdraw from the Lima Group?

At the time of writing, the Trudeau government has not issued a statement on the Bolivian election results. Neither has the Trump administration. Irrespective of when an official statement is issued, the response (or lack thereof) is already far slower than the rapid recognition of the coup perpetrators last fall, when Trudeau fell in lockstep with Trump. It will be the second major humiliating defeat for the Trudeau government on international policy this year. On June 17, the activism of thousands of Canadian citizens and hundreds of global intellectuals contributed to Canada’s failed bid for a UN Security Council seat. This was in part because of the Trudeau government’s regrettable position on Latin America.

With the partial reshaping of the geopolitical landscape in the region, would this not be an opportunity for Trudeau to withdraw from the Lima Group and recognize the rightful leaders of both Venezuela and Bolivia?

The need for a reassessment of Canada’s foreign policy—which the UN vote and now the MAS victory illustrates—may very well earn some support in parliament. For example, as soon as the Bolivia election results were made public, NDP MP Niki Ashton tweet. Canadian parliamentarians would be wise to follow her lead.

Arnold August is a Montreal-based journalist and the author of three books on Cuba, Latin America, and US foreign policy. His articles have appeared in English, Spanish and French in North America, Latin America, Europe and the Middle East, including occasional contributions to Canadian Dimension.

This article written by Arnold August, originally appeared on Canadian Dimension on October 19, 2020.