COVID-19 and the great lockdown triggered a mass migration from analog to digital and highlighted that access to the Internet is crucial for socio-economic inclusion.

High-speed Internet is key for working from home, for children’s education when they can’t attend school in person, for telemedicine, for benefiting from social support programs, and for enabling access to financial services for everyone, especially for those living in remote areas.

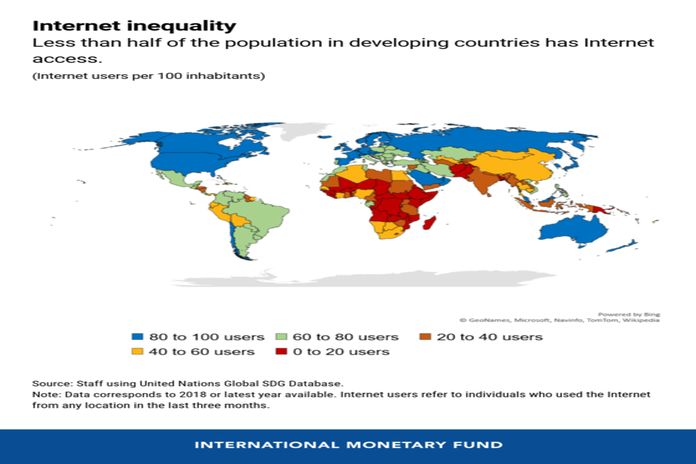

Still, Internet usage remains a luxury: half of the world’s population does not have access to the Internet, either through a mobile device or through fixed-line broadband.

As the map in this chart of the week shows, the digital divide—the gap between those who have Internet access and those who don’t—is more like a chasm, both within and between countries.

Advanced economies like the United States, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Canada have the highest access rates. Big emerging economies show large disparities in the proportion of Internet users in their populations, which range from about two-thirds in Brazil and Mexico to about one-third in India.

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa, followed by many in emerging and developing economies in Asia, are among those with the lowest access to the Internet despite being world leaders in mobile money transactions. There is also a large variation in Internet connectivity by firms in sub-Saharan Africa—only about 60 percent of businesses use email for business compared to about 85 percent in Europe and Central Asia.

Wider inequality

The lack of universal and affordable access to the Internet may widen income inequality within and between countries.

- Within countries. Income inequality and inequality of opportunity may worsen—even in advanced economies—because disadvantaged groups and people who live in rural areas have more limited Internet access. The disparity between men and women in their labor force participation, wages, and access to financial services may increase where there is a gender gap in access to the Internet. This could be the case in many emerging and developing countries where fewer women than men own a mobile phone.

- Between countries. The relatively low Internet access might depress productivity in emerging and developing countries. IMF staff research (PDF) finds that a one percentage point increase in the share of Internet users in the population raises per capita growth by 0.1-0.4 percentage points in sub-Saharan Africa. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates that having reliable Internet allows some businesses to continue operations amidst lockdowns, which keep economies running.

So, how can policymakers support affordable and universal access to the Internet?

Governments can foster a digital-friendly business and regulatory environment for the private sector. This can be instrumental to accelerate and finance investments in infrastructure.

Government support, for instance by ensuring the Internet investment is complemented with universal electricity access, is essential. In addition, subsidies may be needed so that all households—including disadvantaged groups and those in rural and remote areas—have access to quality Internet, and to ensure there is no digital gender gap. For example, in response to the COVID-19 crisis, the governments of El Salvador, Malaysia and Nepal have introduced Internet fee discounts or waivers (PDF).

Policies should also be geared to closing the Internet gap for firms. Broadening small businesses’ access to financial products such as loans will allow these firms to undertake productive investments in information and communications technology. Governments could also see fiscal savings from digitalization. They can lower the public cost of tax compliance through greater access to taxpayer data and improved spending efficiency, which in turn, may help financing these policies.

Given the increasing role of the Internet for the economy and for accessing public services, policies to foster an inclusive recovery must aim to tackle the digital divide within and between countries.

![]()