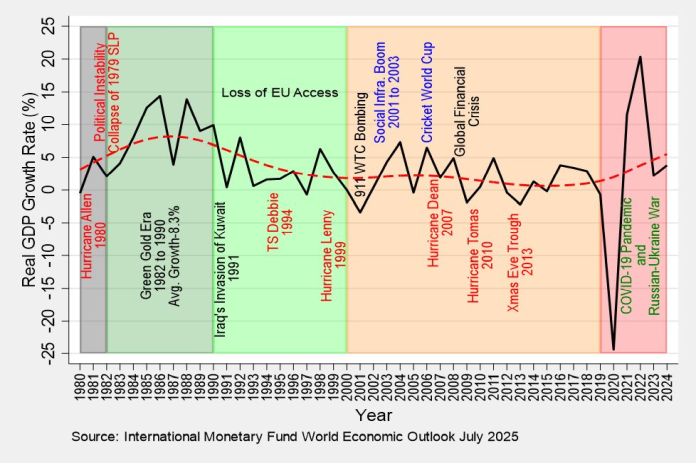

The chart that follows offers more than a sequence of numbers. It tells, in compressed form, a short yet compelling story about our national journey since political independence. To be sure, no single line traced across time can fully capture the complexity, the struggles, or the collective aspirations that have shaped a people. Yet, for all its limitations, GDP nonetheless provides a useful starting point, a broad gaze, of sorts, from which we may attempt to make sense of our economic progress and ask, with honesty, whether growth has truly served the deeper purpose of development and met, in equal measure, the socio-economic demands of Saint Lucia.

Of necessity, any serious analysis must look beyond the surface of the figures and interrogate the character of the growth it records. The essential question is not merely whether an economy has grown, but whether the quality of that growth has been worthy of a nation’s development aspirations and responsive to the deeper needs of its people. What follows makes plain my conviction that growth of this kind: low, volatile, and occurring in sporadic bursts and usually following the onset of shocks, is wholly insufficient to transform Saint Lucia’s economy or to advance the social progress to which our people rightfully aspire.

It is worth noting that there was a time in our post-independence history when economic growth was not an abstraction confined to tables and reports, but a lived reality that carried with it a sense of shared advance. Between 1982 and 1990, Saint Lucia recorded its most vigorous period of economic expansion, with growth averaging close to eight per cent. This was not the fleeting relief of recovery after crisis, but the product of deliberate effort and genuine expansion in the productive sectors of the economy. Yet what followed should have troubled us deeply. With each passing decade, that growth was not merely reduced; it was diminished by nearly half, until what remains today is a shadow of what was once possible.

In seeking to understand our economic journey, I have found it necessary to give it structure. One that does not reduce history to numbers alone but recognizes the forces that have shaped our collective experience. Saint Lucia’s short economic story may therefore be understood through a sequence of defining tests: a political test at the moment of nationhood; an era of terms of trade erosion and structural transition; the ascendency of tourism as the engine of growth and the economy; the intrusion of terrorism into the global order; the recurring shocks of tropical storms; and, increasingly, the turbulence of a changing and uncertain geopolitical landscape. Together, these forces have not merely influenced our economy; they have tested our resolve, our institutions, our way of life and our vision of development.

But, if we are to be honest with ourselves, we must acknowledge that Saint Lucia, once regarded as a standard-bearer/GIANT within the OECS, no longer occupies that commanding position. More troubling still is not merely the loss of that standing, but a disquieting failure to fully apprehend the reality before us and the unsettling absence of urgency with which this reality should be met.

We find ourselves contending with growth that is too weak to lift all boats, and with a debt burden that steadily narrows our room to manoeuvre. For the entirety of the first quarter of the twenty-first century, Saint Lucia has remained effectively confined within a middle-income trap, growing, but not transforming; advancing in appearance, yet stalled in substance. We confront levels of crime and gun-related violence that erode trust, corrode community, and challenge the long-held narrative of our region as a zone of peace. At the same time, a persistent deficit in skills condemns too many of our people to low wages and constrained opportunity. Productivity remains stubbornly low, even as the cost of doing business continues to rise, placing enterprise, employment, and national confidence under constant strain.

Our economic and tax base remains narrow, leaving the state vulnerable and the burden unevenly shared, while our exposure to climate hazards grows ever more acute, threatening livelihoods, infrastructure, and fiscal stability alike. Too much of our economic and social infrastructure remains unequal to the demands of a modern economy and a population that is both growing and living longer. Public service delivery, meanwhile, too often falls short of the standards our citizens have not merely come to expect but have an unquestionable right to demand. The promise of upward mobility, once a powerful engine of hope, has slowed, and poverty continues to cast a long shadow over far too many households, with roughly a quarter of our population held in the grip of deprivation.

The unavoidable question, as we bring the first quarter of the twenty-first century to a close, is whether the Saint Lucia we inhabit today is, in any meaningful sense, stronger, fairer, and more secure than the nation we inherited at the end of the twentieth. This is not a question of nostalgia or blame, but, for sober judgment, for it is in our answer that the measure of our progress, and the urgency of our task ahead, must be found.