By Anne-Marie Gulde-Wolf, Sanjaya Panth, and Shanaka J. Peiris

Economic growth in Asia and the Pacific is poised to slow more than previously estimated this year amid headwinds from the war in Ukraine, a resurgent pandemic, and tightening global financial conditions.

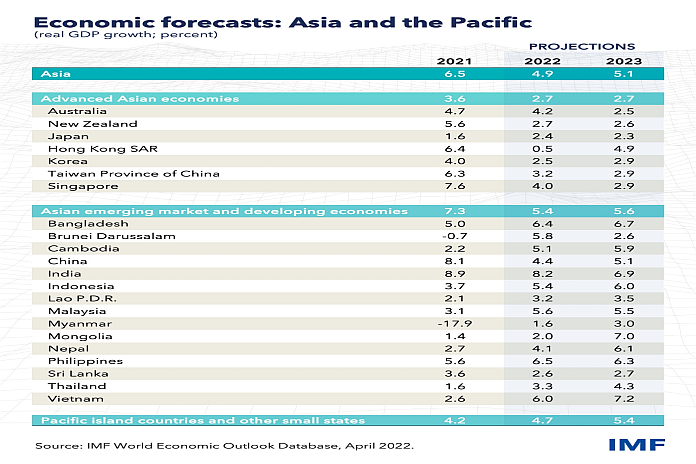

Regional gross domestic product will expand by 4.9 percent, 0.5 percentage points less than we forecast in January and slower than last year’s 6.5 percent growth rate, according to our latest projections. We also estimate that inflation will rise faster in many countries, though from relatively low levels.

Slower growth and rising prices, coupled with the challenges of war, infection and tightening financial conditions, will exacerbate the difficult policy trade-off between supporting recovery and containing inflation and debt.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will pose the biggest challenge for economic growth, with the region’s advanced economies hurt most by reduced demand from Europe and emerging markets feeling the effects of higher global commodity prices, according to our latest projections.

Our latest World Economic Outlook lowered the 2022 global growth estimate by 0.8 percentage point to 3.6 percent. It reflects a 1.1 percentage point cut for the euro area, now seen expanding 2.8 percent. Because Asia’s advanced economies have strong ties with Europe, the continent’s weaker growth will weigh on external demand and ultimately growth for major regional trade partners like Japan and Korea.

Most of Asia’s emerging and developing economies are net importers of oil, gas, and metals, making them particularly vulnerable to rising global commodity prices. That means that a deterioration in their terms of trade—a measure of prices for a country’s exports relative to its imports—will likely reduce growth, weaken currencies, and worsen current-account balances. High food and fuel costs also add to inflation pressures, especially in lower-income countries where they make up a large share of consumer spending.

Coronavirus infections in most of Asia have retreated from their peaks during the rapid spread of the omicron variant, with mobility indicators approaching pre-pandemic levels. China is the most notable exception to this, as lockdowns in Shanghai and elsewhere idle a wide range of activity and threaten to cause further disruptions to regional and global supply chains. These lockdowns are one reason that we project growth in China to slow to 4.4 percent this year, which will affect Asia’s emerging economies through reduced trade and demand.

Tightening and inflation

Tightening global financial conditions will weigh on economic growth. Government bond yields in major Asian economies have begun rising as the Federal Reserve starts to lift US interest rates. Our forecasts are predicated on the expectation that continued tightening abroad and rising inflation at home will lead many Asian central banks to hike rates themselves, placing a drag on investment.

Risks to the economic outlook include an intensification of the aforementioned three main headwinds.

An escalation of the war in Ukraine would further increase food and energy prices, adding to stresses for vulnerable households and potentially causing social unrest to spread to more countries.

A tightening of US monetary policy that is materially faster or larger than currently expected by markets – or both – would have large spillovers to Asia. If disruptive capital outflows occur as a result, central banks in affected countries could respond through the judicious use of all their policy levers in an integrated fashion. The downside risk of capital outflows is mitigated in countries that have built up strong buffers, but is amplified where high debt conspires with other vulnerabilities.

Finally, a greater slowdown in China’s economy due to broader virus lockdowns or other risk factors such as the continued weakness in the real estate sector, would also have large implications for the region, given trade linkages within Asia.

More broadly, a potential fragmentation of supply chains and added geopolitical tensions will remain risks for the longer term for a region that has flourished in recent decades from rising wealth and other economic gains from globalization.

Strong responses needed

Addressing pressures on growth and managing the difficult short-term trade-offs requires strong and coordinated policy responses that are tailored to country-specific circumstances. Authorities in the region should:

- Protect the most vulnerable from rising fuel and food costs. Social unrest has already flared where these pressures exacerbate vulnerabilities, such as Sri Lanka. Promising regional examples of targeted and temporary protections include a Philippine cash-transfer program and New Zealand’s reduction in public transport fares.

- Anchor medium-term fiscal policy frameworks to ensure debt sustainability. With output gaps still large in many countries, the withdrawal of fiscal stimulus must be well calibrated to support the pandemic recovery. Some countries with the space to do so, including China and Japan, responded to recent headwinds with fiscal measures to support recovery this year. But countries most vulnerable to debt distress will need consolidation sooner, and some may benefit from debt treatment under the Common Framework.

- Tighten monetary policy where inflation is rising faster, such as Singapore, or above central-bank targets, as in Korea. Macroprudential policies should limit financial stability risks amid high household debt levels, including to address significant increases in housing prices in some countries.

- Enact economic reforms to boost long-term growth. This is particularly important in Asia’s emerging economies because they may see the most scarring from the pandemic. Overhauls are needed in several areas to boost productivity, such as non-tariff barriers and product and labor markets. Education reforms are essential to address the long-term effects of school closures, which were substantial in South Asia and low-income and developing countries.

![]()