GENEVA, Switzerland – The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) has today launched a new generation Productive Capacities Index (PCI) to help countries make more accurate diagnostics and measurements of their economic performance.

In turn, this can shape more effective policies and their implementation. The PCI measures countries’ abilities to produce goods and deliver services, which are critical for international trade and global production value chains.

The PCI is available through a dedicated online portal with publications, manuals, resources and tools. It maps the productive capacities of 194 economies and provides a better measure of development than other traditional benchmarks such as gross domestic product (GDP). It’s multidimensional and measures economic inputs and potential as opposed to outputs.

For governments, the PCI is a powerful and practical tool to track progress over time and forge informed policies to plug development gaps. It can help countries respond to a call by UN Secretary-General António Guterres to move beyond GDP and measure the things that really matter to people and their communities.

UNCTAD secretary-general Rebeca Grynspan, said:

“No nation has ever developed without building the required productive capacities, which are key to enabling countries to achieve sustained economic growth with accelerated poverty reduction, economic diversification and job creation.”

UNCTAD defines productive capacities as “the productive resources, entrepreneurial capabilities and production linkages that together determine the capacity of a country to produce goods and services and enable it to grow and develop.”

How countries measure up

The PCI shows that developed economies have higher productive capacity scores, with economies such as Denmark, Australia and the United States leading the pack with an average score of 70 out of 100 on the composite index.

Among developing regions, Asia and Latin America, overall, perform better than the African region. Some economies like Chile, China and Qatar gradually converge towards the performance of developed countries with an average score of 61. On the other extreme are African economies such as Chad, Malawi and Niger, which each register an overall PCI score of below 20.

Countries such as Rwanda, Senegal and Togo showed improved PCI scores from 2018 to 2022, but this better performance has not substantially altered their overall global ranking.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, Barbados, the Dominican Republic and Panama made notable progress in developing their productive capacities during the same period. Similarly, Asian economies such as Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia and Timor-Leste made notable performance gains on the composite index.

But several developing countries from various regions regressed on the composite index. These include Brunei Darussalam, Guatemala, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Namibia, Suriname and Uganda.

A novel approach to measuring development progress

Countries need reliable tools that respond to changing global conditions. In view of the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine and climate change, external shocks increasingly affect countries’ abilities for sustainable development.

While headline economic indicators like GDP capture economic production as a measure of output, the PCI takes a novel approach to measuring development progress.

Originally released by UNCTAD in 2021, the newly updated index is an enhanced data-driven tool to help countries improve their development policies. It follows a robust, revised methodology and updates the data for the period 2000 to 2022.

The PCI has helped several developing countries to assess their productive capacities and develop programmes to plug gaps.

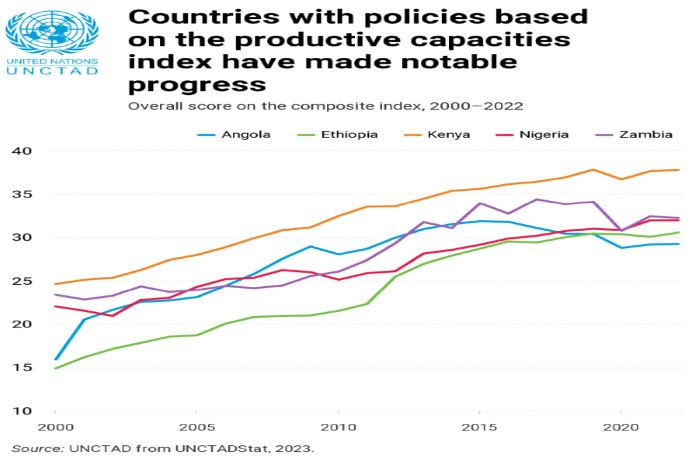

Angola, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria and Zambia have used the PCI to put in place data-driven and evidence-based policies. Cambodia, El Salvador, Malawi, Mongolia, Mozambique, Senegal and Zimbabwe are following suit with UNCTAD’s support.

Productive capacities are key to long-term development

By measuring the economy from an input perspective across eight core components of productive capacities, the PCI more fully captures economic potential and highlights key areas for development policy focus. These are natural capital, human capital, energy (electricity), ICTs, structural change, transport, private sector and institutions, which are mapped using 42 indicators.

Stronger productive capacities in these areas can help countries move towards long-term national development goals and achieve international targets like the Sustainable Development Goals.

Paul Akiwumi, UNCTAD’s director for Africa and least-developed countries, said:

“The new generation PCI is a timely contributor to development policymaking. Against the turbulent global economic backdrop, reliable, up-to-date and accurate data can help governments react by focusing on the most pressing development issues.”

The new PCI also helps shape long-term planning. “What we can diagnose and show with the PCI are the underlying factors that are holding back countries from meeting their trade and development potential, such as key infrastructure gaps in transportation, ICT development and energy,” Akiwumi added.