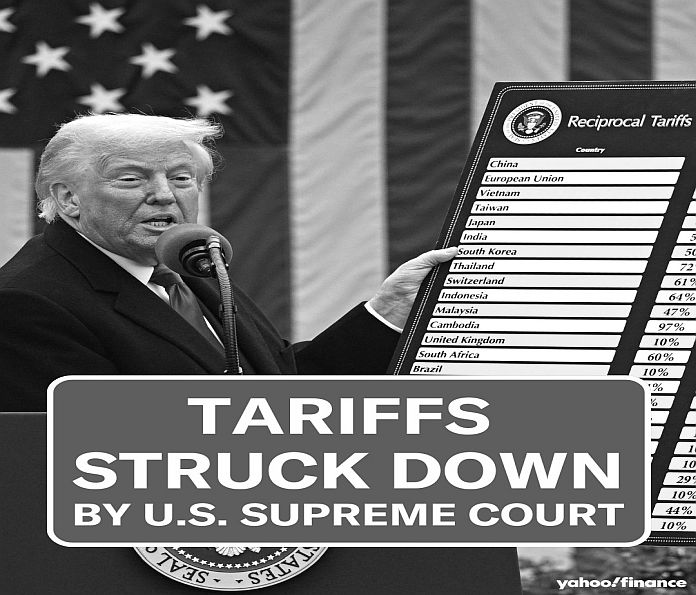

On February 20, 2026, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS), in a keenly-awaited decision, struck a lethal blow to the Trump Administration’s Liberation Day emergency powers tariff regime. Asked to determine whether the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) authorises the president to impose tariffs, the Supreme Court in Learning Resources Inc v Trump (2026) held by a 6 to 3 majority that the 1977 Act does not grant the President such power.

Although US law contains provisions in various pieces of legislation delegating to the president the ability to impose tariffs for national security reasons, the SCOTUS reaffirmed that it is Congress which has taxing (including tariff imposition) authority under the US Constitution. This ruling has, therefore, served as a check on presidential power, reaffirms the separation of powers, and is also welcomed news for countries whose exports now face higher tariff barriers in the US market. However, as this article will show, the fight is not over yet.

How did we get here?

From his first term, tariffs have been a central plank of president Donald J. Trump’s neomercantilist America First Trade policy under his pledge to “Make America Great Again”. In his second term, the President upped the ante by seeking to claim broad tariff imposition powers under the 1977 IEEPA. This Act provides the US President with economic tools to deal with “an unusual and extraordinary threat” from a foreign origin and with respect to a declared national emergency. It should be noted that the statute does not specifically identify tariffs as one of these tools.

In his infamous ‘Liberation Day’ Executive Order of April 2, 2025, the president declared a national emergency with regard to two identified “unusual and extraordinary threats”: first, the flow of illegal drugs from Canada, Mexico and China which he argued had created a public health crisis and second, the US’ “large and persistent trade deficit” which had led to a “hollowing out” of the US’ manufacturing base and undermined critical supply chains. The government’s central argument was that the IEEPA gave the president the ability to implement tariffs to tackle these “threats”.

More importantly for the Caribbean, president Trump imposed a 10 percent “reciprocal tariff” on nearly all countries globally, and additional tariffs on others. While Caribbean countries were subject to the 10 percent blanket tariff, Trinidad and Tobago’s ‘reciprocal’ tariff rate was increased from 10 percent to 15 percent, while Guyana was subject to an additional rate of 38 percent which was subsequently reduced to 15 percent after diplomatic negotiations. Importantly, these are the two Caribbean Community (CARICOM) countries with which the US has a trade deficit. However, in 2025, the US registered a trade surplus with Trinidad and Tobago, according to US Census data.

These tariffs were implemented regardless of whether there was a free trade agreement or other preferential trade arrangement in place between the US and that country. Many Caribbean countries, had hitherto enjoyed non-reciprocal duty-free access to the US market for most of their goods under the Caribbean Basin Initiative and its constituent pieces of legislation. However, these new tariffs meant that goods which were originally tariff-free were now subject to at least 10 percent tariffs, unless they were among the list of exempted goods which were later expanded.

Impact of the tariffs

It is importers which pay import tariffs and not foreign countries. Importers can either absorb the costs, or, as they often do, pass them on to consumers.

Many US small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) were particularly impacted. In an MSNBC interview in the aftermath of the ruling in his favour, the CEO of Learning Resources Inc, stated that his business had lost millions of dollars because of these tariffs in 2025. His is one of several US businesses which are now seeking refunds from the Federal Government for the tariffs they paid (plus interest), and which Penn-Wharton projects at US 175 billion.

US householders also were among those impacted by the tariffs, which a Tax Foundation report estimated as amounting to an average tax increase of US $1,000 per household in 2025 and a projected US$1,300 in 2026.

Moreover, the tariffs have not even achieved their stated objectives. Although tariff revenue has increased, the US trade deficit still remains wide, and the merchandise trade deficit reached a record high in 2025. This is not surprising as many US businesses and households in the first half of 2025 rushed to bring in imported products before the tariffs came into effect.

What does this ruling mean for the Caribbean and what next?

This ruling only applies to the IEEPA tariffs and not the national security tariffs under other statutes, such as the Section 232 (Trade Expansion Act 1962) and 301 (Trade Act of 1974) tariffs. However, on the face of it, the SCOTUS ruling is good news for Caribbean countries, which were caught under the now-illegal IEEPA tariffs.

The US remains the region’s largest trading partner, the main market for extra-regional exports, and enjoys a large trade surplus with the Caribbean. Tariffs on Caribbean goods make these goods less price competitive in the US market, and therefore impact Caribbean firms exporting to the US, and ultimately pose challenges for Caribbean economies. The ruling, therefore, appears to be a ray of hope.

However, this matter is not over yet. In his address on the SCOTUS’ decision, president Trump has stated that he will sign an executive order to impose a 10 percent global tariff “over and above” existing tariffs under section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974. Although section 122 tariffs can only be implemented up to 15 percent and for a limited period (150 days unless Congress votes to extend them), it introduces more uncertainty for both US importers and foreign exporting firms to the US which hoped that this ruling would have given them some certainty.

As we await the Trump administration’s next steps, much uncertainty exists, and Caribbean businesses must continue to monitor developments and adjust accordingly. At the regional level, CARICOM and its associate institution, the Caribbean Private Sector Organisation (CPSO), have been proactively keeping their hands on the pulse of constantly evolving US trade policy developments, including engaging in diplomacy to advocate for the region’s interests.