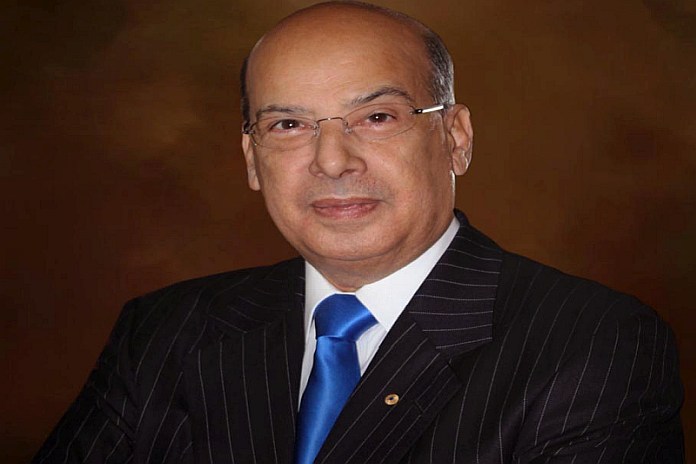

By Sir Ronald Sanders

The saying, coined by the Latin poet, Horace, that “you too are in danger when your neighbour’s house is on fire” is particularly relevant now in relation to Latin American countries which are the closest neighbours to the member states of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM).

There has been a marked increase in deadly violent incidents in Latin America, linked to organized criminal gangs. This includes the assassination of the leading candidate in Ecuador’s presidential elections and the murder of two other politicians over the last month.

Fernando Villavicencio was assassinated on 9 August, eleven days before the 2023 Ecuadorian general election on August 20, at which he was polling in second place to win the presidential contest. He had a fearless and courageous stance against organized crime and corruption which have increased dramatically over the last three years. He was shot in broad daylight.

It is generally accepted in Ecuador that Villavicencio was the victim of organised criminals who feared that he would crack down upon their activities if he won the presidency. Ecuadorian police reported 3,568 violent deaths between January and July this year. There are some neighbourhoods that outgunned, unprepared and unpaid police dare not enter.

According to the International Crisis Group (ICG), there have also been upsurges in violence in Argentina, Costa Rica, Panama and Paraguay. The ICG reports that “Even in Chile and Uruguay, long considered bastions of regional calm, crime is skyrocketing. In 2022 alone, murders in Chile increased by 32 percent, reaching a record high. Similarly, incidents of rape and the illegal use of firearms rose. In Uruguay, a transit nation for cocaine smuggling, a surge in crime last year saw a 25 percent increase in murders. Feeding the region’s epidemic of violence is the unchecked flow and circulation of illegal weapons.”

In Mexico, the number of criminal groups doubled between 2010 and 2020. In El Salvador, over the last two years, the government of president Nayib Bukele locked up more than 70,000 persons with what has been described as “little semblance of due process.” The purpose was to eliminate criminal gangs that have tormented the country for years.

The governments of the neighbouring states of Honduras and Guatemala have praised the El Salvador model as one “worth emulating.” And, Honduras president, Xiomara Castro, announced her own crackdown on gangs.

Both the governments of El Salvador and Honduras have been criticised for human rights abuses in relation to these responses to violence and crime. But analysts say that the security situation is “pretty dire”, therefore the general population recognise human rights abuses in El Salvador, “people are so sick of crime that they’re willing to sacrifice democracy or personal freedoms if it means that they can sleep easy at night.”

These events in Latin America are taking place in the CARICOM neighbourhood; it would be foolhardy to ignore them or to pretend that Latin America is some distant part of the world that matters little. Latin America envelopes the Caribbean, bound by shared waters.

Crime, particularly involving gangs linked to drug and human trafficking, knows no borders. Much like communicable diseases, it can spread unchecked across nations. Scholarly research shows that enterprises of organized crime are far better funded and organised than the law enforcement agencies of all the CARICOM countries combined. In this connection, it is time that the Caribbean pays serious attention Latin America, not only for occasional forays into trade and tourism opportunities, but to safeguard against the spread of crime which now terrorises people and murders politicians and government officials who stand in their way.

The limited attention given to Latin America is evident in the Caribbean media’s lacklustre reportage and commentary. Such events as are reported in the press, radio and television are captured from the Internet or international broadcasters such as CNN and the BBC. Consequently, the Caribbean public receives news of Latin America that CNN and the BBC deem important or relevant.

In any event, CARICOM countries cannot ignore matters in neighbouring states in Latin America, particularly as connections, through modern-day technology, are being freely used by criminal elements to organise and strengthen their own networks. This begs the question concerning what structured links are there between law enforcement agencies in Latin America and CARICOM?

The OAS, through several of its programmes, offers the opportunity for discussion and formulation of actions by law enforcement bodies throughout the hemisphere. And while the OAS forum is beneficial, it should not be the only means by which the burgeoning problems of crime, gangs and violence are addressed between Latin American and Caribbean authorities.

Much more is needed; the fire is raging in some Latin American states, and it is also blazing in Haiti. The Caribbean must try to stop the spread before it happens. This requires focussed national and regional attention by governments and law enforcement agencies within CARICOM, but it also needs a structured relationship with Latin American states to learn from their experiences and to exchange information.