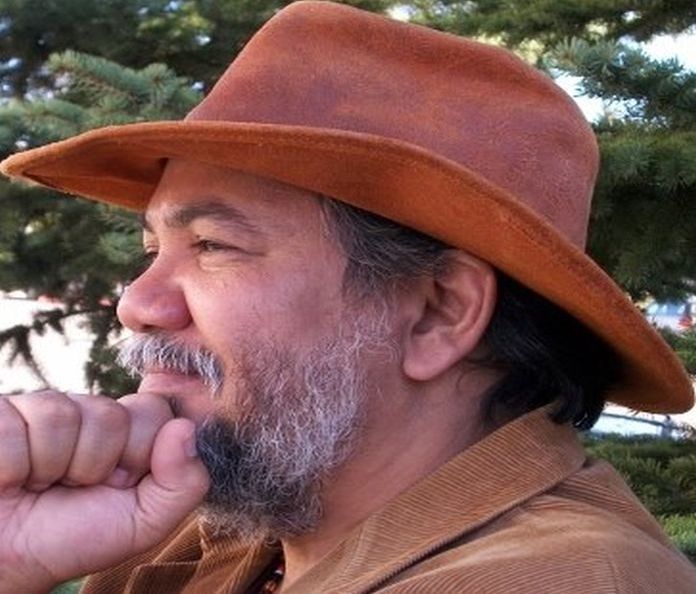

By Johnny Coomansingh

It was only in the year 1999 that the ‘Domestic Violence Act’ (Act 27) came into being in Trinidad and Tobago. For the generations prior to the implementation of this act, domestic violence in all its terror and horror was extant on the landscape like nobody’s business. According to the act, ‘domestic violence includes physical, sexual, emotional or psychological or financial abuse committed by a person against a spouse, child, or any other person who is a member of the household or dependent.’

Emerging from the Gender and Child Affairs Unit, a preliminary enquiry was conducted titled: ‘Domestic Violence in Trinidad and Tobago Lifetime Experiences.’ The research found that “… despite increased efforts of advocacy and service provision, Trinidad and Tobago continues to witness the most excessive use of violence against women.” In light of this fact, this article portrays a snippet of the turmoil and torment that my family experienced.

Below is an adaptation of an excerpt from my book titled: Seven Years on Adventist Street; a part of my story:

“Infested with fleas and bed bugs, the house where we lived for some of the most trying years of my life was no bed of roses. I reckon that somewhere in the grand scheme of things, an invisible hand allowed me to survive some horrid years as a child. Sadness was always mingled with childhood gladness. (Prior to our abode at Adventist Street, we lived at Picton Street, Sangre Grande).

Words are inadequate to fathom the atrocities meted out upon my mother and her children in this one-bedroom apartment at Picton Street. Sometimes I reflect on what I can remember about my father. It is probable that he was possessed of some foul spirit. At such an early age, my mind could not decipher my father’s actions. To me, he was a living nightmare.

There were many nights when I would wake up crying. The noise of a never-ending battle between my mother and father raged on. In fact, all of us cried “mammy, mammy, mammy” while my daddy was beating the daylights out of my mother during the night. My bed of rags on the floor was no comfort, and the fleas, mosquitoes, and bedbugs did not make my passage through the night any easier.

I did not know why my father beat my mother. No one could intervene or serve as a referee. If she complained, it could mean more “licks” (physical abuse) and verbal attacks. Those were the dark and miserable days for women like my mother who simply ‘managed’ domestic violence the best they could. In those days, many women in Trinidadian society accepted acts of spousal abuse as normal events. Even today some still do. I guess my mother stayed in the relationship because of us. I cannot see any other reason.

I was too young to understand the incomings and outgoings of elder folk. I could not with my childhood eyes see the wheels that turned in this father/mother relationship. Hearing the rasping push and pull of a Nicholson file in the act of sharpening a cutlass (machete) in the wee hours of the morning outside the bedroom door was enough to make any child want to stain his undergarments. One night with cutlass in hand, as he pressed to push open the back door, my mother said to my father, “You will have to chop the child first,” as she held her last baby above her head. I was very young at the time, but how could anyone ever forget the traumatic moments of such a scene?

This was no soap opera, no fiction, no dream; this was my reality. My father constantly threatened to chop or shoot my mother. Yes, my father had a gun, a 16-bore shotgun. With this gun he felt powerful. He felt he could bring anyone to their knees in obedience. As we all are aware, crisis situations require crisis solutions.

The day came when my mother left my father with all of us. He created a pot of the worst-smelling soup and told us to have some. That very day he told us that he was going to kill himself and drank some black liquid out of a Milo can. A little later we learnt that he had tricked us. ‘Chin,’ the Chinese grocer next door, told us to remind our father to return the Pepsi bottle. He drank a Pepsi from the can and pretended it was poison.

Why would a father do such a horrible thing to his children? What type of spirit guided this man? The Holy Bible says, ‘Honor thy father…’ Is it really possible to honor a father of this nature? It’s easy to see that the hovel where we lived in destitution was a literal hellhole, a dark patch in my life. Did this scenario during the early stages of my existence make of me a stronger person; a better person?

In our backyard he raised rabbits. Instinctually, the neighbor’s dogs would come over, night after night, rip up the wire mesh, and kill a couple of rabbits. My father was always enraged about these ‘stray’ dogs and the damage they were doing to the hutch and to his animals. He spoke with his neighbours but despite his warnings, they made no effort to control their dogs. Without hesitation, he shot the dogs. Such was my father’s way of solving problems.

There was this day when my older brother and I received a horrible beating from my father. The horror of this beating event could be likened unto a nasty medieval flogging in the street. I do not think that any human would beat even a dog the way we were beaten. Held by an arrogant, enraged and evil father, two little boys were inhumanely and brutally flogged for sharing a mango bitten by one of our friends. Apparently, my father got into a rage when he lent his heavy crosscut saw to some fellows who went to the recreation ground located on Ojoe Road, Sangre Grande.

As I later understood, they borrowed the saw to build a pair of football goalposts. It is quite possible that they forgot their promise to return the saw as soon as they had finished with their construction project. We saw my father pacing up and down, fuming and mumbling. Then he spied us sitting on the concrete edging next to a fence. It was a bright and happy day for us. We had a juicy mango, and bit into the fruit with glee. My brother was just six years old. I was four.

Enraged, he grabbed two of us with one hand and dragged us into the yard in front of the house. The house was not fenced, so we were exposed to the road for all to see. My father instructed my eldest brother to cut whips to beat us. The whips were not to his liking, so he threw them back at my eldest brother in a rage telling him to cut something better; a firmer sapling or branch that would not shatter on our soft skin. Mercilessly, he set upon us and flogged us as we squirmed and grimaced in the dust. I must have fainted under the blows, for at one point I did not feel anything. My mother could not have intervened lest she be beaten too. The sting of the whips was unbearable.

After the beating, my mother gave us warm baths and applied some Iodex (a type of liniment) on the wheels. The wheels were horrible; long shameful blue-black streaks all over my little body. They were on my arms, legs, back, belly, and sides; such pain. Surviving this beating at such an early age framed in me a different concept of my father. I believed that no child should be treated as he treated us. I literally shut him out, and he became an object of hatred. I cannot say it any other way. Was I wrong to engender such resentment?

‘The longest rope has an end’ is an adage I have committed to memory. We also have a similar saying in Trinidad. ‘Give maga (meager) goat long rope.’ The idea is that the goat will be only able to graze as far as the rope extends. Finally, the night came when my father left; his rope had come to an end.

My father really ‘woke up’ when my eldest brother threw a heavy glass vase at him and cut him on his chin. Not long after that incident, my father made his mind up to leave. With no fanfare, he took his cabinetry tools and left. The only tool that remained was his big and heavy crosscut saw. The saw had been stored behind the roll-top safe in the kitchen and later fell through the rotted flooring. It was found rusted and covered in mud under the house. I made sure that it remained with me as a solid reminder of my father’s arrogance.

There is much more to add to this nasty piece of drama. I could never say that I am proud of my father. It has been said that ‘writing heals.’ It is almost cathartic. I must at all cost purge myself of my childhood experiences. Sometimes, I ask myself, why did I have to pass through all this horror? Why couldn’t my childhood moments in life be happier? Why did I have to manage all this mayhem?

As I write these lines, more and more I am defining my mental construct; the me that is resident inside of me. I am now aware that I was imperceptibly denied the normal pleasantries of sweet childhood. Such pleasantries were daily being replaced by rancor, confusion, and misery when my father dwelt with us. If there were a way to erase childhood memories, I would certainly seize the opportunity to quickly obliterate mine. Do we ever question what happens to a child’s fertile and precious mind while growing up under such conditions?”