By Philip Barrett and Sophia Chen

What happens to stock markets when social unrest such as mass protests and riots occurs? Are investors scared off by the disorder? Or are they buoyed by the prospect of positive, popular change in response to unrest?

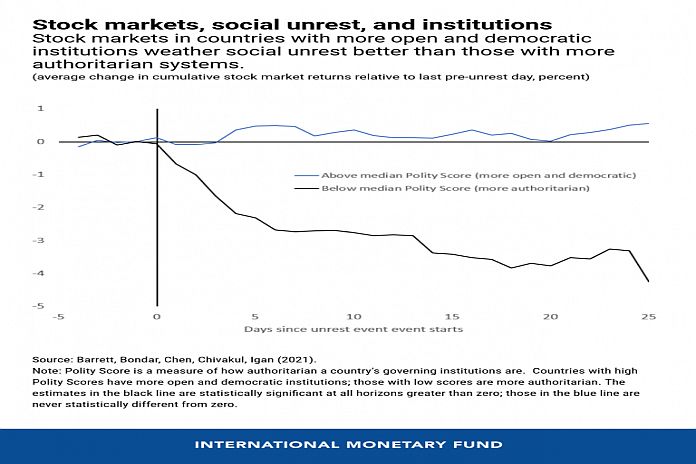

Our chart of the week, drawn from our recent IMF staff working paper, uses a new dataset of 156 social unrest events during 2011–20 to shed some light on these questions. It shows that in countries with more open and democratic institutions, social unrest events have a negligible impact on stock market returns (blue line). But in countries with more authoritarian regimes, the effect is large and negative: on average, stock market returns fall by 2 percent within three days, and by about 4 percent in the following month (black line).

These findings are consistent with real-world examples. For instance, stock markets in France a country with strong and open institutions were largely unmoved in the days after the Yellow Vest protests began in late 2018.

Of course, differences across countries could occur for many reasons other than political institutions. So, we also check that this relationship holds after accounting for other factors that might be correlated with the degree of institutional authoritarianism, including the severity of unrest and the country’s income level.

To dig deeper into what sort of institutions might be important, the paper runs further experiments using the six measures of social and political institutions that form the World Bank Governance Indicators. Of these, two factors play a crucial role in mitigating negative stock market reactions to social unrest events: popular participation in government, and the ability of the government to regulate markets in ways that promote private sector development.

What sort of investor behavior might explain these patterns?

One clue comes from the volume of shares traded, which increases sharply following a severe unrest event. As more trades occur when investors disagree on the value of an asset, a higher trading volume typically reflects more uncertainty over the outlook. This result suggests that social unrest affects stock market returns through an indirect information channel rather than via direct disruption to economic activity.

Together, these results imply that in countries with high standards of governance, social unrest does not lead to more disagreement and uncertainty about future economic performance. This perhaps reflects the ability of more open institutions to reconcile divergent opinions and find compromises.

In contrast, this flexibility may be missing in more authoritarian systems. There, institutions may be less able to adapt to social problems, meaning that unrest can lead to rising fears of further uncertainty and deter investors.