By Arthur Deakin

There is no denying that the world’s inflationary pressures and future economic prospects are directly tied to energy-related geopolitics. In early October, OPEC+ signalled their support for a higher oil price by cutting production by 2mn bpd, a clear disregard of America’s requests to keep production stable. OPEC+ claims they are seeking to avoid a supply glut if a recession comes, while the US accused them of siding with Russia. Tensions are frothing.

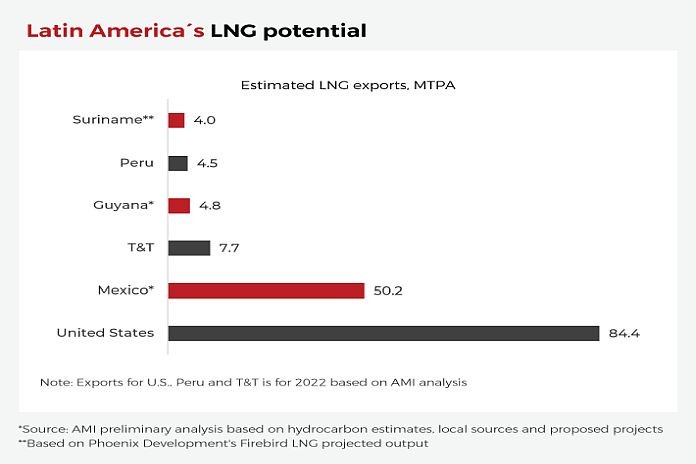

With Russia’s discounted oil and LNG being diverted to Asian buyers, and its gas deliveries to Europe falling by 80 percent, the world’s energy markets have been forced to shift and recalibrate. To substitute the decline in Russian energy supply, Europe has accelerated its renewable energy deployment and increased its net LNG imports—up 65% through the first eight months of 2022. Most of the additional LNG deliveries have come from the United States, who has been able to reroute existing shipments due to flexible contracts. The US is now operating near export capacity at roughly 84 MTPA (million tons per annum), although new projects will increase its baseload capacity by 39 percent through 2025.

American LNG additions will coincide with a major expansion of Qatar’s North Gas Field, bringing online a combined 70 MTPA by 2025 and adding 19 percent to the global LNG supply. Despite those additions, the LNG market will remain structurally tight through at least 2025. Renewable energy, and energy storage, are not being added fast enough to fulfill both the growth in global energy demand and the fall in Russian energy exports, which accounted for nearly 40 percent of Europe’s energy supply in 2021. Latin American countries with substantial gas reserves have noticed this trend and are gearing up to become LNG exporters, a prime opportunity for both companies and investors alike.

Given the complexity and extensive capital needed to export LNG, only two countries currently do so in Latin America: Peru and Trinidad and Tobago. Peru LNG, the consortium responsible for the country’s exports, increased its LNG deliveries by 70 percent in the first half of 2022 – shipments to Europe alone, saw a 46-fold increase. To ensure a constant flow of export revenues, the Peruvian government appears to have discarded the renegotiation of the consortium’s Camisea contracts and has encouraged them to export at full capacity of 4.4 MTPA. As the government narrows in on supplying natural gas to the local population, there are no planned increases for LNG exports in Peru.

Trinidad and Tobago, on the other hand, saw LNG exports decrease 2 percent in the first five months of 2022. Trinidad is struggling with declining gas reserves due to its mature gas fields, unappealing fiscal terms, and overshadowing discoveries in neighboring countries. In an effort to revive its collapsing industry and encourage participation in its next tender, the government proposed an increase in the Investment Tax Credit for energy companies and a reduction in the Supplemental Petroleum Tax (SPT) for new wells drilled in shallow waters.

Trinidad and Tobago’s future prospects, however, remain dire. Unless sanctions on Venezuela are lifted, or a major gas discovery is made, both of which are rather unlikely, Trinidad will see a continued decline of its oil and gas industry. Trinidad’s LNG exports have fallen over 50 percent since 2010.

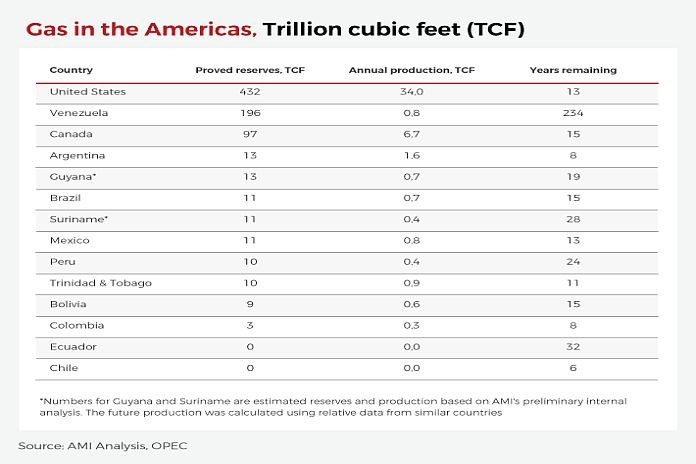

Trinidad’s decline, coupled with Peru’s focus on the domestic market, creates opportunities for new players to enter the LNG export market. Guyana and Suriname, the emerging superstars of the region, could have 13.2 and 10.8 Tcf (trillion cubic feet) of natural gas reserves, respectively, based on AMI’s preliminary estimates. Their miniscule local demand means that there is plenty of excess gas that can be exported via ships or pipelines. Both countries have direct routes to Western Europe and Northern Brazil.

In Suriname, US-based Phoenix Development Company has partnered with the Port Authority of Suriname to develop a U$1.2 billion LNG liquefaction plant and export terminal with a planned output of 4 MTPA. Its chief executive officer said that they are fully funded through to Final Investment Decision (FID), and they will use natural gas that would otherwise be flared as their source of supply.

In Guyana, where the total estimated recoverable resources have surpassed 11 billion barrels of oil equivalent, LNG exports could reach nearly 5 MTPA. This volume alone could replace 4percent of all Russian gas that went to Europe in 2021.

In nearby Mexico, president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) is contemplating eight LNG-export projects, one of which is already under construction. Mexico’s strategic advantage over Suriname and Guyana is that it has a much more developed hydrocarbon industry, an existing pipeline infrastructure that brings in cheap natural gas from the Permian basin, and a direct route to Asia – who is expected to account for nearly 70 percent of LNG demand growth through 2040. The country’s most advanced project is Sempra Energia’s Costa Azul facility in the West coast, which is expected to start shipping 3.2 MTPA of LNG by 2024. In an ideal scenario for AMLO, where all approved and proposed projects become a reality, Mexico could add 50 MTPA of added capacity to the LNG market. This would make it the fourth-largest LNG exporter in the world.

To avoid putting the cart before the horse, there are several things that need to be considered. More broadly speaking, LNG projects require vast amounts of capital and complex expertise, two things that are hard to find in emerging markets – especially when a recession is looming and the US Federal Reserve is rapidly increasing rates. More specifically in Suriname, the country has yet to receive a FID (Final Investment Decision) for any of its hydrocarbon explorations. Although this is expected to happen in 2023, the decision has been continuously postponed and reflects TotalEnergies’ hesitancy to fully commit to the country. Suriname’s more stringent fiscal terms regarding its oil profit-sharing agreements (compared to neighbours), as well as its multi-year double-digit inflation, debt defaults and political patronage, have also contributed to an uncertain outlook.

In Guyana, the oil is already flowing, but the amount of associated gas discovered has been largely under wraps. If the gas does materialize, foreign investors will have to navigate a strict local content policy and a relationship-driven political environment. Mexico developers, in specific, won’t be able to develop projects without a formal partnership or an endorsement by a state-controlled entity. Timing is also an issue. LNG plants take at least four years to become fully operational and can overlap with new administrations. Not only will these projects see increased competition from other LNG assets in Canada and the US., but they will also face growing renewable supply and declining oil demand. To move forward with these assets, it is paramount to make these assets “transition ready,” allowing them to operate with and transport lower carbon fuels such as hydrogen and biofuels.

Prior to the pandemic, energy experts were concerned about an oversupply of gas and stranded LNG assets. Now, developers and governments are rushing to build LNG import and export terminals with little to no regard over costs. How long will this last? It is difficult to say. What is guaranteed, is that renewable capacity and energy storage will expand substantially, EV adoption will continue to grow, and energy efficiency will reduce energy demand. Only the most strategic fossil fuel assets will survive this transition.